Sometimes a tale’s ending is so ghastly, we might be tempted to change it in the retelling. This is the final installment of a four-part series that explores little-known samples of local lore perhaps suitable only for the Halloween season and those with sturdy digestive systems. The first installment introduced us to the legend of James Wolverton and to Will Trauger, who was tumbling down a mineshaft. In the second installment we met a group of Three Rivers Boy Scouts searching for Wolverton’s grave. And, in the third installment we followed Joel Rivers Woolverton to his final resting place. In this final part of the series, we face Will’s ghastly end.

By Laile Di Silvestro, 21 October 2019, 3RNews

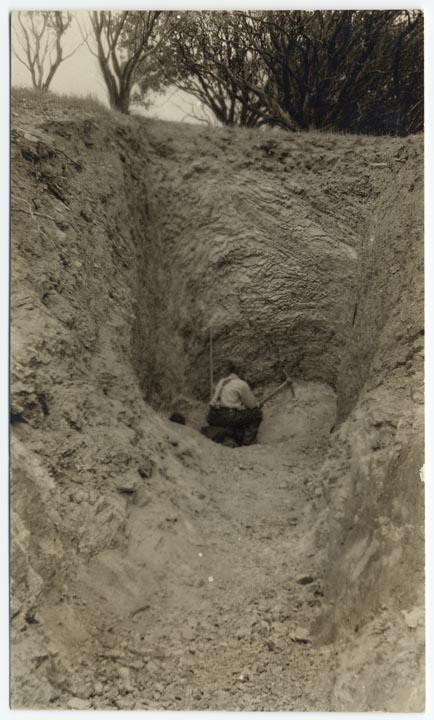

When we last left Will Trauger, it was the dark night of May 23, 1903, and he had just reached the bottom of a forty-foot mineshaft.

He wasn’t alone. Will Kenna had landed beside him, which wasn’t surprising as the men were seemingly inseparable. They lived together in a small cabin. They mined together when they weren’t drinking, and they drank together when they weren’t mining. They were about to become notorious.

Infamy wasn’t new to Will Trauger. Indeed, he had been born into it.

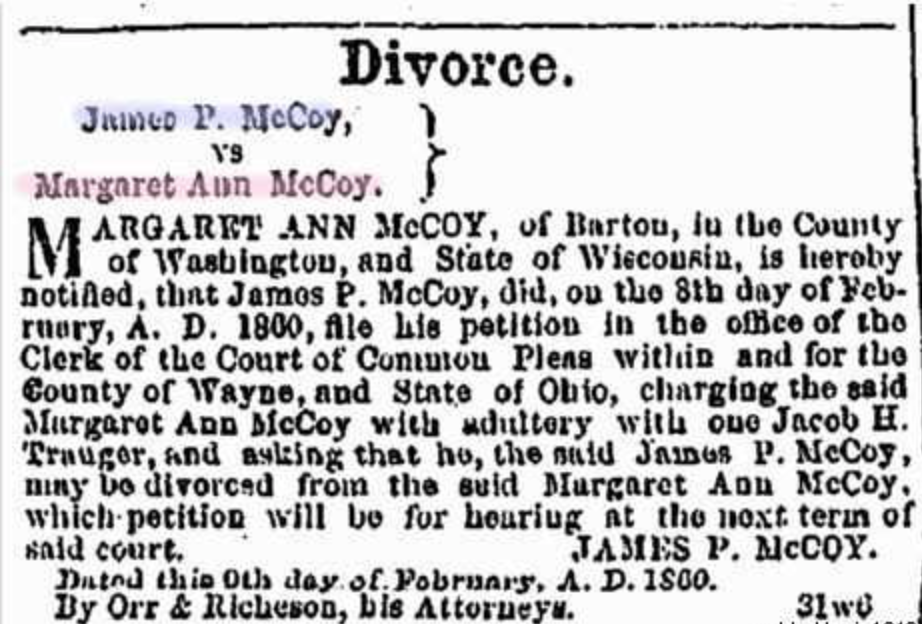

He started out life in 1859 as William McCoy. His mother, Margaret McCoy, was living with her husband, James, in Congress, Ohio, at the time, as was the presumably ardent Harry Trauger. It didn’t take James long to conclude that Will was not his son, and he filed for divorce from Margaret in 1860 on the grounds of her adulterous relationship with Harry.

Margaret was cast out of her home and denied custody of her two older children. Harry Trauger was no help. He left Ohio for California, abandoning his mercantile and farming businesses for a relatively unsuccessful career as a miner.

Margaret and Will boarded with other families for a time while she developed a career as a women’s hat-maker. By the age of twenty, Will had abandoned her too. He took on the name of Trauger and headed west to find his father.

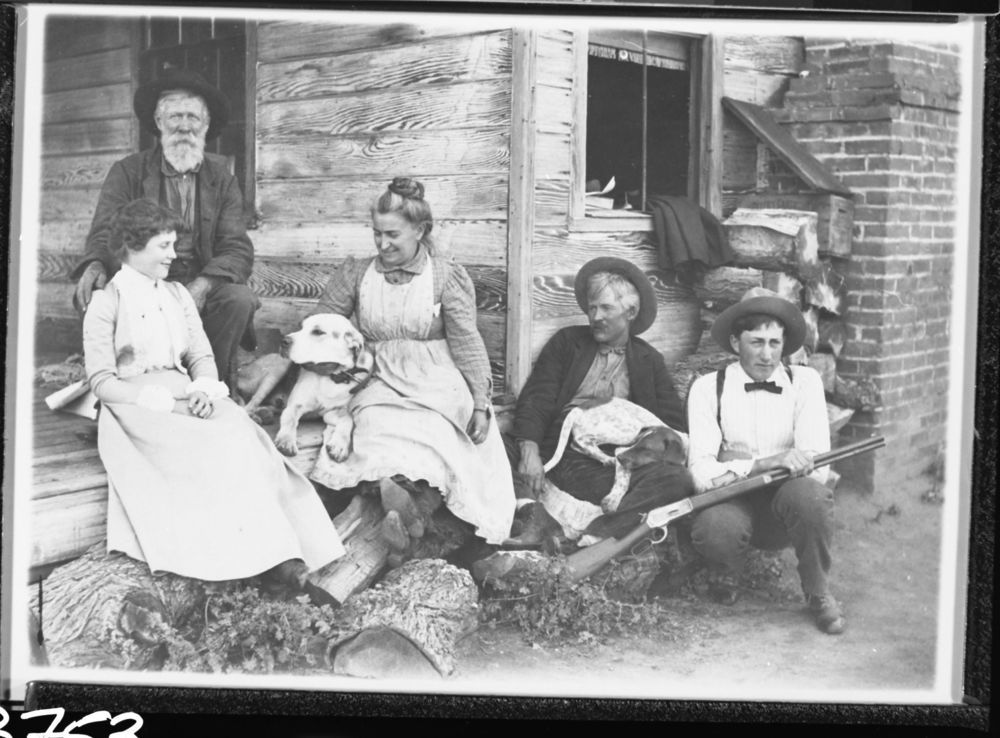

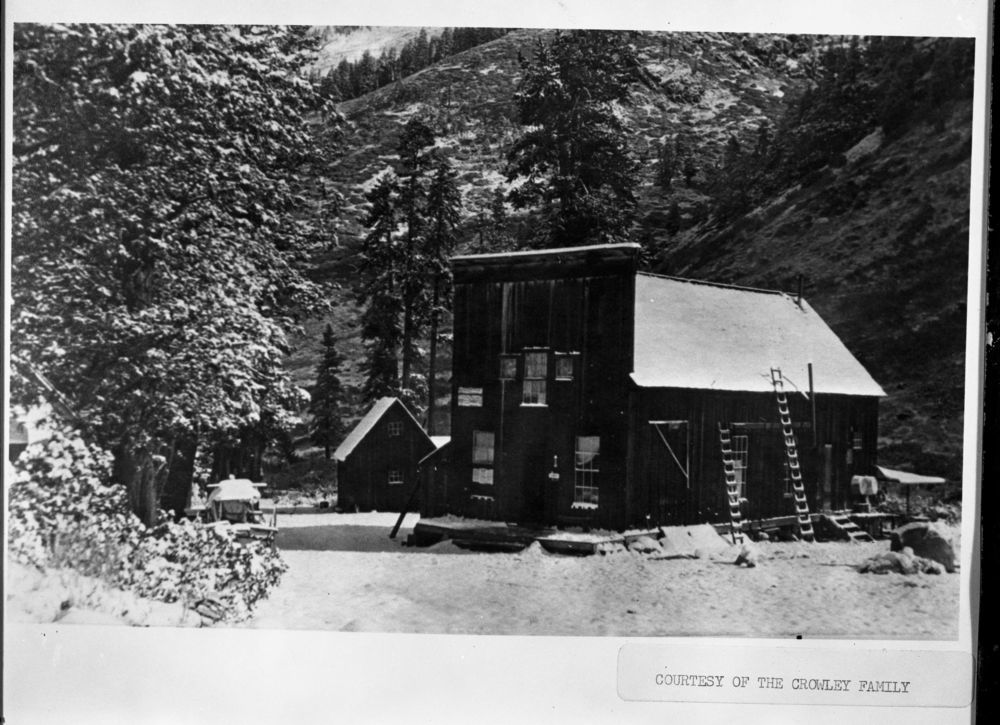

Harry Trauger was at this time living with his indomitable wife Mary on the Last Chance Ranch. He had found a job as supervisor for the duplicitous New England Tunnel and Smelting Company in Mineral King, and was now mining, tending the books as the mining district recorder, and earning a reputation as a drinking man.

When Will arrived, the silver rush in Mineral King was all but over, but he was able to find work as a mining laborer for Arthur Crowley and helped him set up a summer resort in the Mineral King valley. For several years he and Harry also received a contract from the County of Tulare to maintain the Mineral King Road after the road was declared “a disgrace to an enlightened community” in 1893.

Will made a home on the land near the bridge over the East Fork of the Kaweah River, the home where he brought Joel Rivers Woolverton to be tended by his stepmother, and the land where he helped lay Woolverton to rest in 1893.

Will was a tall man at 5 feet, 10½ inches, with blue eyes, fair skin, and hair that had turned prematurely grey. Like his father, Will developed a profound relationship with the bottle.

He partook in intoxicated fistfights and even ended up in jail on one occasion with several of his friends. He was a favorite with the local newspapers, however, due to his exuberance for life.

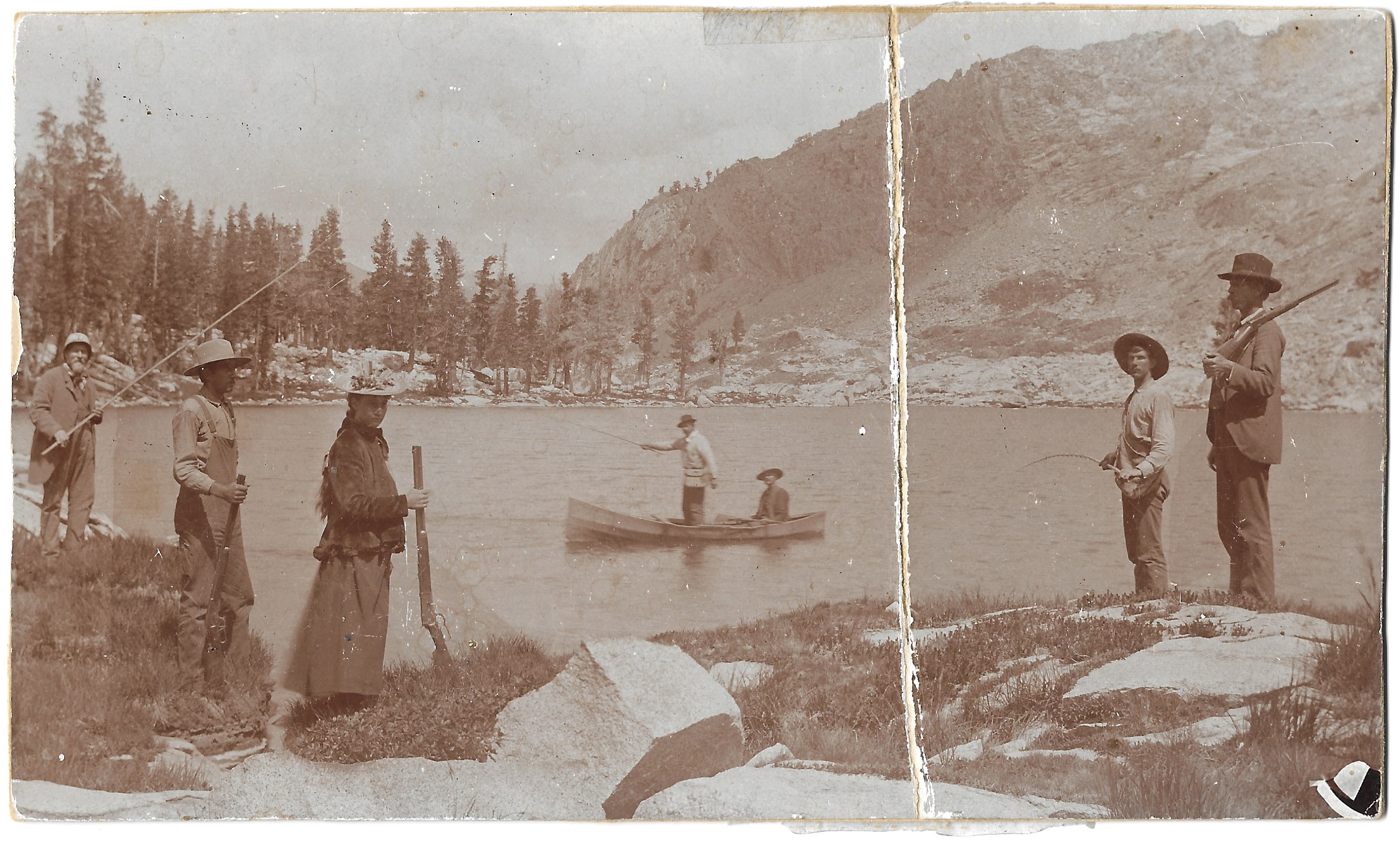

Will enjoyed taking friends to Mineral King, where they hunted and ate roasted bear head, built and launched a boat in Eagle Lake, and carried trout to Mineral Lake in a coffee can.

In 1897 Will Trauger left Tulare County for the mines of El Dorado. There he, Will Kenna, and their small dog set up house in a little cabin in Volcanoville. It was only a half-mile distance from Phillip’s Place, a drinking establishment that they frequented when they weren’t seeking their fortunes in gold.

On the eve of May 23, 1903, the men stumbled together out of the establishment with their dog. The spent Rubicon Mine was in the vicinity, but in the dark only the dog saw its forty-foot shaft.

The impact broke both of Will Trauger’s thighs and one of Kenna’s legs.

They had one pistol between them. They fired all their bullets up the shaft and shouted, to no avail. Eventually their voices gave way.

Their absence was not noted because they were known to go missing on account of being drinking men. Kenna purportedly kept track of the passing days on a slip of paper.

According to Kenna, after several days, our Will realized he would die. He wrote a note to Harry and Mary and provided verbal instructions on the eventual disposition of his possessions.

He then became delirious and attempted to eat Kenna, who suffered numerous bites and clawing. According to Kenna, Will died after nine days in the shaft.

On the eleventh day, the little dog was able to attract the attention of George Morrow of the Gregory Mine. Morrow followed the dog to the abandoned shaft. There he found Will dead and Kenna extremely weak. Kenna’s leg was rotting, and it was deemed unlikely that he would live long.

How could Kenna have survived almost eleven days without food and water? We can easily imagine. The state of Will’s body prompted an inquest, which mercifully resulted in a verdict of accidental death.

Will’s ending was too ghastly for Mary and Harry Trauger. They told their friends and neighbors that Will had died honorably in a mining accident in Alaska.

Over time, Will became the “angel” Mary’s son, best known for his contribution to the new resort at Mineral King. And as we have seen, Joel River Woolverton’s story was improved as well. History renamed him James Wolverton and created a hero worthy of the biggest tree in the world. A hero who fought with General Sherman to preserve the Union; a hero who met John Muir and helped preserve the giant sequoias; a hero who stood lookout to protect the new Sequoia National Park from the ravages of livestock. A hero who stayed at his post even while facing his death. …

What do we gain and lose from resurrection of the real stories? Certainly we lose the legend, but perhaps we gain an essential human connection through the less heroic and sometimes macabre truths. Regardless, we retain the story of a community that tends and celebrates even the least mighty among us.

Thus ends this series. The search for our roots goes on, however. One of the most rewarding aspects of historical research is the joy of discoveries that augment or refute what we thought we knew. If you have perspectives, stories, or evidence that would enhance or alter the tale that has been laid out in this space, please contact us.

Acknowledgments:

I am grateful to Sarah and John Elliott for hosting this series, and for their ongoing support, encouragement, and editorial expertise.

About the Author:

Laile Di Silvestro is a historical archaeologist who resides in Three Rivers, California, just outside Sequoia National Park. Her current project is researching and documenting the 19th-century mining activities in the Mineral King area of Sequoia National Park.

1 thought on “J. Wolverton and the Ghastly End 4”

Comments are closed.