Part 3: In the Shadow of the Mountain. One man’s journey from a WWII incarceration camp to the second highest peak in California.

The Order

In the previous installment, Giichi Matsumura had immigrated to California from Fukui, Japan, along with his new bride, Ito, just before President Coolidge signs the Immigration Act of 1924 into law, effectively ending Japanese immigration. The young couple settled in Santa Monica Canyon, where Giichi and Ito started a new life and a new American family.

According to the 1930 U.S. Census, Giichi Matsumura lived with his wife, Ito; their three young children; Giichi’s younger brother, Tadao; and their 60-year old father in a small house they rented for $20 a month. Situated on land owned by the Marquez family that dated back as far as anyone could remember, the Matsumuras became close friends with their landlords, who were original settlers of Santa Monica Canyon.

Life in Santa Monica Canyon

Although the house had no electricity and was undoubtedly crowded with three generations living there, life was pleasant in the idyllic seaside canyon. After Masaru was born in 1925, the young couple was blessed with a second son, Tsutomu, late in 1926. A third son, Uwao, was listed as an infant on that 1930 census report. Giichi, a quiet, hardworking man, was a gardener who worked for private employers, just like his father.

By the time of the next census in 1940, Giichi was listed as the head of a household that comprised just him and Ito and their (now) four children, adding daughter, Kazue, in 1935. Giichi’s brother and dad were apparently now living in different housing. It is unclear if Giichi’s family still lived in that same house near the old Marquez adobe, but daughter Kazue would later recall their house lacked electricity, so that would seem to be the case.

Another thing the Matsumura children remembered was the rustic, country feel of the canyon. Masaru remembers walking to school.

“There were no houses, no nothing around here,” he said. “I used to run through the cornfields.”

Kazue remembers sliding down the steep banks of the canyon’s hillside on a piece of cardboard.

While there were a fair number of Japanese immigrants in nearby parts of Santa Monica, and large Japanese communities at the Terminal Island fishing village or in downtown Los Angeles, the Matsumura kids were among the only Japanese Americans attending Canyon School. They made friends easily. Classmates Masaru and Ernie Marquez were best friends all through school.

One other thing the census reports from those days noted was their citizenship status. Giichi and Ito were listed as resident alien. Their country of birth (Japan) and year of immigration (1924) were also duly noted. Such first generation immigrants were known as Issei by the Japanese. The Matsumura children, American-born and thus citizens, were Nisei, the term the Japanese used for this second generation.

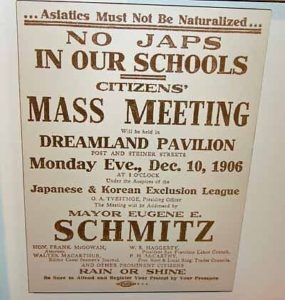

While life may have been fairly harmonious for the Matsumura family in Santa Monica Canyon, there was a growing resentment against the Japanese American community in the United States, especially in California. This dated all the way back to fears of a “yellow peril” after the unexpected military victories of the Japanese over the Russians in 1904-1905 and echoed the Chinese Exclusion Act and jobs protectionism of the 1880s in California. Growing Japanese militarism and a sense of competition for jobs amongst the laboring class during the Great Depression ramped up anti-Japanese sentiment during the 1930s.

Japan’s aggressions

In the fall of 1931, Japan began occupying Manchuria. Japan’s plans to create a Pacific Empire were counter to the interests of the United States. Diplomatic relations began deteriorating. In 1935, the Office of Naval Intelligence warned of Japanese espionage rings in various West Coast cities. Lists were compiled of suspects of Japanese heritage who were deemed sinister enough to warrant surveillance, were potentially dangerous, or even just exhibited pro-Japanese tendencies. Everyday people such as Japanese language teachers, martial arts instructors, travel agents, and newspaper editors made this list.

In the fall of 1941, when war seemed with Japan seemed imminent, President Roosevelt asked the State Department to determine the degree of loyalty of residents of Japanese descent. The report, authored by Curtis Munson, basically concluded there was no Japanese “problem” on the Coast and that there likely would be no armed uprising of Japanese.

Munson further stated that “for the most part, the local Japanese were loyal to the U.S., or at worst, would hope that by remaining quiet they can avoid concentration camps or irresponsible mobs.” Events later that year would render any calming force Munson’s report might have had utterly forgotten.

Round Up

On December 7, 1941, Japan bombed Pearl Harbor. For the Matsumura family, and every person of Japanese heritage on the West Coast, that fateful day that President Roosevelt later said would “forever live in infamy” changed their lives, utterly and completely.

Within hours of that attack, the FBI began rounding up Issei leadership of the Japanese Americans from that list of those supposed potentially dangerous subversives. The round-up was swift and frightening to the Japanese American community.

Many of these so-call possible subversives were held for years under no formal charges. Giichi’s daughter recalled decades later that her father, thankfully, was not among those rounded up by the FBI in the early days following the bombing of Pearl Harbor. But that didn’t mean that the war would not touch their lives.

Within days after Pearl Harbor and America’s declaration of war, the West Coast was officially designated a theatre of war. This declaration made possible much of what followed for the Matsumura family and so many others.

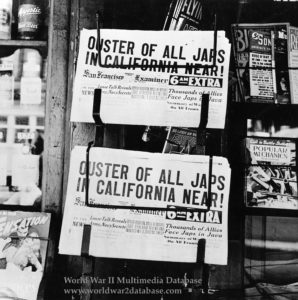

Agitation in the press stoked fears and egged on the government to take drastic steps. Hearst columnist Henry McLemore wrote in January 1941 that “I am for immediate removal of every Japanese on the West Coast to a point deep in the interior. I don’t mean a nice part of the interior either.” After suggesting they be herded off to the badlands, and he expressed a desire for them to be “pinched, hurt, and hungry,” the caustic writer admitted that “personally, I hate the Japanese.”

Syndicated columnist Walter Littmann offered a more sober argument in a February 12, 1942, article, outlining the perceived threat from a “fifth column on the Coast,” where he warned that “the Pacific Coast is in imminent danger of a combined attack from within and without” and a “Japanese raid accompanied by enemy action inside American territory.”

It wasn’t just newspaper editorials that stoked the race prejudice and war hysteria. Even Los Angeles mayor Fletcher Bowron said, “We cannot run the risk of another Pearl Harbor episode in Southern California.” Fear that Japan could soon invade the West Coast gripped America, as did fast-spreading misinformation.

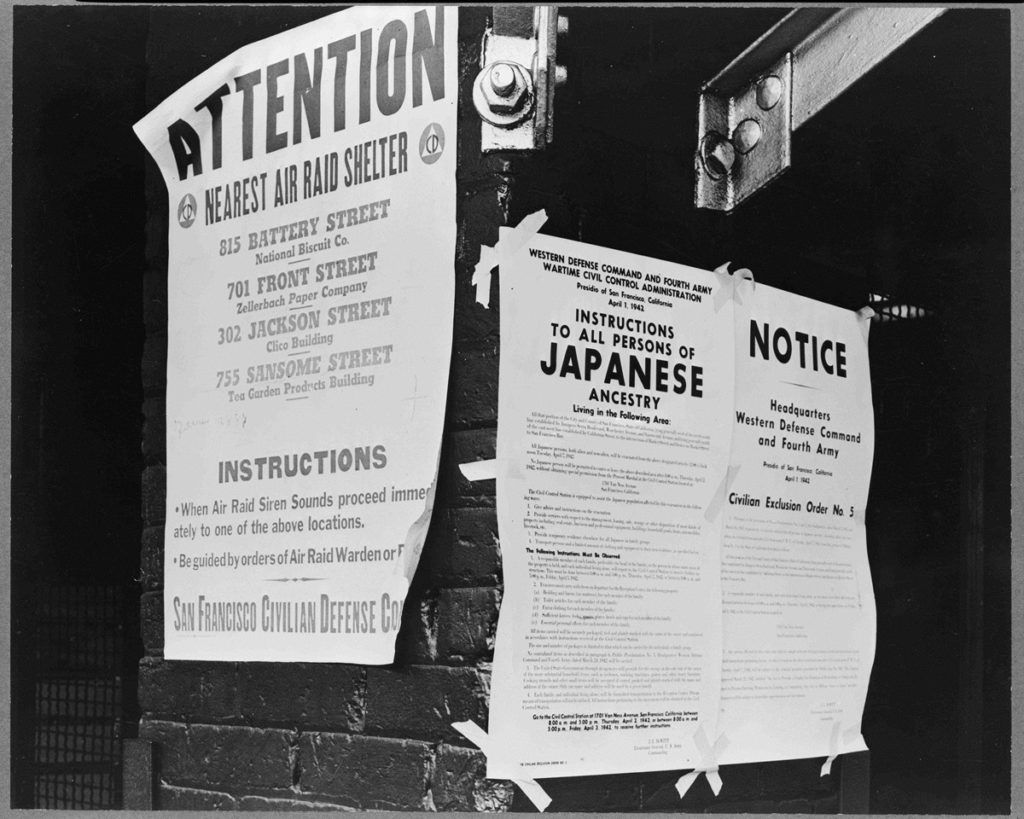

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, empowering the U.S. Army to designate areas from which “…any or all persons may be excluded.”

That order, to borrow FDR’s phrase, would itself forever after “live in infamy.” It is today considered a blight on his reputation. It heralded a dark chapter in our nation’s history.

In March, the War Relocation Authority was created. By this time, the writing was clearly on the wall (indeed, literally, as the above photo indicates) for any Japanese American living in California. In addition to the early round-up of suspected subversives right after Pearl Harbor, entire communities were beginning to be subject to exclusion orders and relocation. The Japanese fishing village at Los Angeles’s Terminal Island was one of the first Southern California evacuations, forever wiping out an ethnic community’s entire industry.

In April, Civilian Exclusion Orders 7, 8, and 9 were issued, calling for the relocation of residents of Japanese descent from several regions of Southern California, including Santa Monica Canyon. The Matsumuras were told they would have to leave.

The Matsumura children had to leave school. Ernie Marquez felt that his school chum, Masaru, was being unfairly punished, since Mas had no more connection with Japan than Ernie had with Mexico. “We were both born and raised in the canyon.”

The family was given very little time to prepare. Giichi didn’t even have time to sell his car, a prized possession, so ended up giving it away. Most families did the same, some giving up businesses, homes, pets. Everything was lost to relocation.

Kazue, only six years old at the time, remembers they could only bring one suitcase. How does someone pack everything they own and might need in one small suitcase? But her main memory of that otherwise painful time was being excited about the bus ride. It was a long ride on a big bus, all the way to Manzanar.

* * *

On October 24, 2019, Associated Press reporter Brian Melley followed up his initial story about the discovery of a skeleton on Mount Williamson with startling news of just whose remains the two hikers may have discovered. Authorities were reluctant to confirm or give any credence to the theory Melley (and soon many other reporters and journalists) proffered.

Inyo County Sheriff’s Office insisted the theory was just one of many possibilities they were investigating. They stated they planned to conduct DNA tests, but would not reveal if they had obtained a comparative sample to prove identity.

(Melley’s reporting, however, discovered they already had collected a sample from a suspected relative.)

DNA testing from bone matter is a complicated process and results could take months. So in the meantime, the Sheriff’s Office would offer no further comment.

At the far western edge of the Manzanar National Historic Site, lying just outside where the barbed wire fences once were, is the camp cemetery. A National Park Service interpretive sign tells its history and notes that 150 people from the camp died during incarceration and most had been buried in the Manzanar cemetery, with its distinctive memorial obelisk standing sentry.

The interpretive copy also informs anyone who bothers to read it that there was one man who died during the final days of the camp while exploring the nearby Sierra. His name was Giichi Matsumura, and he is “buried high in the mountains above you.”

In the next installment, the Matsumura family arrive at the Manzanar War Relocation Center and we get a glimpse of what life was like behind barbed wire for them and the 10,000 others incarcerated for years at the high desert camp in the shadow of the mountain.

Read Part 4.

Read the entire series here.