Part 6: In the Shadow of the Mountain. One man’s journey from a WWII incarceration camp to the second highest peak in California.

The Storm

In last week’s installment, we met members of the Manzanar Fishing Club. Giichi Matsumura, acquainted with these men, had just convinced them to let him join a planned excursion high into the mountains above Manzanar. For them, it was a chance to fish the mountain lakes one last time perhaps. For Giichi, it was a chance to paint new landscapes as his years of forced captivity in the wind-swept, desert camp were apparently coming to a close.

John Muir once described a summer storm he’d experienced in the High Sierra: “A range of bossy cumuli took possession of the sky, huge domes and peaks rising one beyond another with deep cañons between them, bending this way and that in long curves and reaches, interrupted here and there with white upboiling masses that looked like the spray of waterfalls.” It was, to the famed naturalist, both beautiful and imposing.

To most people caught out in such an onslaught, it would be a frightening mix of lightning, thunder, rain and, on rare occasions at high elevation, snow and deathly freezing cold. Anyone who has spent appreciable time in the Sierra high country knows that summer storms can hit quickly and without warning. And while a blizzard in August is a rare thing even high above timberline, it has been known to happen. Sometimes with deathly consequence.

* * *

By the summer of 1945, those who had been incarcerated at the Manzanar War Relocation Camp were technically free to leave. A War Defense Command proclamation lifting the West Coast exclusion orders and restoring the rights of Japanese Americans to return to their former communities had gone in to effect in January of that year.

But for the Matsumura family, like so many others who had been forcibly relocated to the desert facility years earlier, they had nowhere else to go. Having lost all their possessions in the forced evacuation, they had little or no resources. Having lacked regular income for so long, money was in very short supply or non-existent.

Furthermore, there was great uncertainty as to what welcome they might receive upon re-integration into the outside world. What were the chances that Giichi Matsumura, who had worked as a gardener in Santa Monica Canyon before the war, would be able to re-acquire clients upon return from camp? Especially as Japan was still, in July 1945, stubbornly fighting an endlessly destructive war against the United States and resentment of his very race might overwhelm common decency.

So for the Matsumura family and so many others, Manzanar remained their last best option, imprisoned now more by the culmination of circumstances than by barbed wire or armed guard towers.

Giichi was known to sketch and paint watercolor pictures all over the camp whenever he had free time. When his wife, Ito, learned of his plans to accompany a group of fishermen from the camp up to the mountains, she didn’t want him to take his pencils or art supplies. His daughter, Kazue, later recalled that her mother feared “if he started drawing, he’d get lost.”

Even though Ito refused to give her husband his art supplies, Giichi was able to borrow some from someone else. On July 29, 1945, Giichi and the group of fisherman set off toward Mount Williamson. It would be a long, grueling hike up over Shepherd’s Pass and into the lake-dotted bowl on the other side of that looming peak. They would be gone for days.

“Before he left,” Kazue recalled, “I knew he was never going to come back. I had that feeling, but I never told my mom. I knew he was never going to come back.”

Exactly what happened up on the mountain is hard to know exactly. Filmmaker Cory Shiozaki offered perhaps the best account in a newspaper interview late last year. Shiozaki told how once the group of several men, led by Amos Hashimoto, made it to Williamson Bowl, Giichi chose to do some painting while the others went on ahead to fish at another lake. They would all meet back up after fishing to return to Manzanar.

“During that time, a sudden snowstorm broke… a complete whiteout. The main group that followed Amos took refuge in a cave.”

After the snowstorm, the fishermen searched the immediate snow-covered area but could not locate Giichi.

“They assumed he must have gone back to camp,” Shiozaki explained. But when the group got back to Manzanar, they learned Giichi had not come back.

Tragically, little Kazue’s premonition — the feeling that she’d had — had come true.

Days later, two search parties made up of some of the fisherman plus two of Giichi’s oldest sons and his brother Tadao went back up to the mountains to try and find him. Kazue remembered that her “brothers and them went up to search,” but that her mother didn’t want them to go. Upset as she was, Ito didn’t want anybody else to get hurt.

On August 25, 1945, the Manzanar Free Press ran a notice “In Appreciation – To the residents of Manzanar for their kindness in searching for Giichi Matsumura.” It was signed by Ito Matsumura and her father-in-law, Katsuzo Matsumura.

In a remarkable 2018 oral history interview conducted by Rose Masters, a park ranger at the Manzanar National Historic Site, Kazue Matsumura recounted the still-vivid memories of a little girl concerning her missing father.

“I had a dream about him,” Kazue said. “And I saw some places. And I told the people that went up there, I dreamt he was in one of those holes or something. ‘Yeah, there’s a place like that, we’re going to go see.’ And they found his jacket there. I was little, but I remember that.”

Sadly, his jacket was all they found.

A few weeks later, two hikers, Mary and Paul DeDecker from nearby Independence, discovered Giichi’s remains and contacted authorities. The fishermen and Matsumura family members of the earlier search parties banded together once again, this time as a burial party.

Kazue recalled that her mother sent a sheet up to cover her dad. The burial party made their way back up over Shepherd’s Pass and into Williamson Bowl, now knowing exactly where to find Giichi’s body.“They covered him up with rocks and created a card with a prayer pasted onto the grave site in typical Japanese fashion.” Shiozaki recounted that “they got his fingernail and hair clippings and brought those back for his wife.”

While we will perhaps never know exactly how Giichi died up on that mountain, his daughter Kazue, more than 70 years later, would describe it almost as if she were actually there. Whether she was just an imaginative little girl or eerily clairvoyant is not completely clear.

In Kazue’s words, “the storm started coming, he starts rushing, trying to get back to camp, and that’s when he fell… ’cause it was raining, and all those rocks, you could slip on those… and he hit his self, bad, and he had a bloody nose, and he fell back again, and he died.”

* * *

“The bowl is no joke,” Tyler Hofer offered in an account of his 2019 trek up Mount Williamson. It was an area where you wouldn’t want to drop anything, lest it be lost in the myriad craggy crevices underfoot. And God forbid you make one careless misstep and crack your skull in the resulting topple.

And when Tyler and his hiking companion, Brandon Follin, later found skeletal remains on the lake-dotted stretch of tumbled, jagged rock, it appeared to both like the skull had been fractured on one side. Tyler surmised from some kind of blunt-force trauma, perhaps. This just added to the remarkable mystery of their high-altitude and rather grisly discovery.

* * *

Kazue, who was ten years old when her father died, remembered how hard his disappearance and death was on her mother.

“She was really scared,” Kazue remembered. “I felt sorry for my mom, you know. She couldn’t eat or anything… And her hair, it turned white when we couldn’t find him. She had black hair and it turned white all of a sudden.”

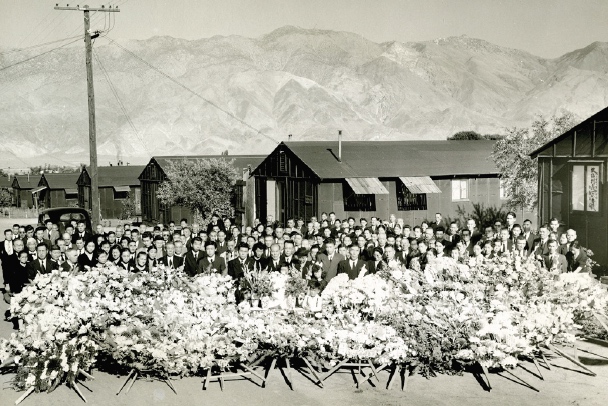

At Manzanar’s Block 18 Buddhist church, a funeral ceremony was held for Giichi Matsumura. The funeral was attended by many. Large wreaths were constructed with crepe-paper flowers made by hand. But there was no body. Giichi would remain at his final resting place high up on the other side of Mount Williamson.

By the time of Giichi’s funeral, the war had ended. Japan surrendered to the United States on August 14, 1945. Manzanar would only remain open a couple more months, giving time for the families and people staying on to make some kind of arrangement to find a place to live. Life for those incarcerated had utterly changed, and their difficulties were far from over.

“We all had to get out of camp,” Kazue explained. “We took the bus, and our friend in Los Angeles, he gave us a ride to my aunt and uncle’s house and we stayed there for two years, I think. That was hard on my mom. We didn’t have any other place to go.”

The difficulties that lay ahead for the Matsumura family and so many other Japanese Americans after incarceration at relocation camps in the American West is another story, perhaps yet to be told here.

* * *

In October 2019, after having climbed Mount Williamson and making their gruesome discovery on the hike, Tyler Hofer and Brandon Follin checked with the Inyo County Sheriff’s Office and left Independence, facing a long drive back to the San Diego area where they both lived. Heading south, they saw the sign for the Manzanar National Historic Site.

Tyler had driven past the site on Highway 395 many times but had never taken the time to stop.

“I am not really sure why we decided to stop that day,” Tyler explained. “Maybe there was something drawing us to that place.”

Maybe, like a little girl named Kazue who’d lost her father 75 years earlier, he was just a little bit clairvoyant.

On January 3, 2020, DNA testing confirmed that the skeletal remains they’d discovered on Mount Williamson were indeed those of a Manzanar incarceree who had died in the summer of 1945. His name was Giichi Matsumura and his story has finally been told.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author would like to thank the following for their input, assistance, and support on this project: Brian Melley of the Associated Press, who first broke this story; Rose Masters at Manzanar Historic Site, who kindly sent me a DVD of her remarkable interview with Kazue Matsumura; Thomas Storesund, who put me in contact with two of Giichi’s granddaughters; Cory Shiozaki for speaking with me about his research making The Manzanar Fishing Club; and Carma Roper at the Inyo County Sheriff’s Office for answering my questions.

Source materials for this series were voluminous and included contemporary newspaper accounts (including the Manzanar Free Press, which is available online), numerous books and magazine articles, census reports, and extensive online resources such as those provided by Densho: The Japanese American Legacy Project and the wonderful NPS-provided Manzanar: Historic Resource Study. Information on the Matsumura family was also found in the 1997 book Santa Monica Canyon: A Walk Through History.

I would like to personally thank Tyler Hofer and Brandon Follin for speaking with me at length about their memorable trek up Mount Williamson.

And a special heartfelt thank you to Lori Matsumura and Lisa Matsumura Reilly. I hope I have adequately honored their family history, and that the attempt here to tell their grandfather’s story, as well as the story of Manzanar and Japanese American incarceration, has in some small way succeeded in illuminating a dark chapter of history.

Read the entire series here.