The planet’s 4th largest tree by volume was dedicated Aug. 10, 1923, in honor of President Warren G. Harding, at the hour of his funeral.

By Sarah Elliott, 16 April 2019, 3RNews

The President Tree is the fourth largest tree in the world. It is easily accessed via the Congress Trail in Sequoia National Park’s Giant Forest.

The President Tree is the fourth largest tree in the world. It is easily accessed via the Congress Trail in Sequoia National Park’s Giant Forest.

The Congress Trail is a paved loop trail that begins and ends at the General Sherman Tree parking lot. It is a self-guiding trail and, although the most famous of the named trees are also graced with carved, wooden signs, there are pamphlets available at the trailhead that correspond with numbered markers along the trail that discuss various natural features of the forest.

It is also advised to travel in this area with a map in hand (available at park visitor centers). There is a network of trails criss-crossing the Giant Forest plateau and though most junctions are marked, it’s easy to become confused.

To reach the President Tree, take the Congress Trail — which is marked with a sign just east of the Sherman Tree — into the forest past the Leaning Tree, where the route then turns south.

In less than a tenth of a mile, the trail crosses Sherman Creek. Although above the return loop portion of the trail, it can be intermittently seen below.

The trail climbs gently, and in just over one-quarter of a mile, crosses another tributary of Sherman Creek. A trail junction is reached in under a half-mile that connects with the return loop.

Stay left here and continue to gradually ascend on the Congress Trail south. At just over three-quarters of a mile, the trail meets the Alta Trail.

Stay left here and continue to gradually ascend on the Congress Trail south. At just over three-quarters of a mile, the trail meets the Alta Trail.

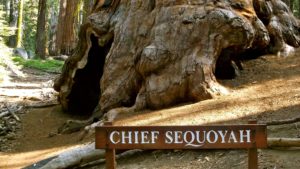

This is where a slight detour will allow a glimpse of the beautiful Chief Sequoyah Tree. Instead of turning right on the short portion of the Congress/Alta trails just before they again go their separate ways, continue instead straight, crossing the Alta Trail.

This one-tenth of a mile segment is part of the Trail of the Sequoias, a six-mile loop trail that explores the highest reaches of the Giant Forest plateau, as well as Log, Crescent, and Circle meadows, Tharp’s Log, and provides access to several other trails in the area.

About 500 feet south of the Alta Trail on the Trail of the Sequoias, the Chief Sequoyah Tree comes into view. It is reached by a short spur trail that ascends to the left.

The Chief Sequoyah Tree was named in 1928 by Colonel John R. White, park superintendent, for the man who developed an alphabet for the Cherokee people, one of the greatest intellectual feats of all times. German botanist Stephen Endlicher, who originally named the trees sequoia gigantea (the Big Trees are now botanically known as sequoiadendron giganteum) and sequoia sempervirens (coast redwood), did so in Sequoyah’s honor, but changed the spelling to how it appears today.

The Chief Sequoyah Tree was named in 1928 by Colonel John R. White, park superintendent, for the man who developed an alphabet for the Cherokee people, one of the greatest intellectual feats of all times. German botanist Stephen Endlicher, who originally named the trees sequoia gigantea (the Big Trees are now botanically known as sequoiadendron giganteum) and sequoia sempervirens (coast redwood), did so in Sequoyah’s honor, but changed the spelling to how it appears today.

Back on the trail, the President Tree is in sight on the right side of the trail, an easy jaunt of one-tenth of a mile. The President Tree was dedicated Aug. 10, 1923, in honor of President Warren G. Harding, at the hour of his funeral.

Presidents of the United States well understand the checks and balances provided by their various branches, and for this, the President Tree is aptly named. It’s branches are high up, large, and powerful, keeping the main body of the President, its trunk and lifeline, upright and true despite the species’ shallow roots system.