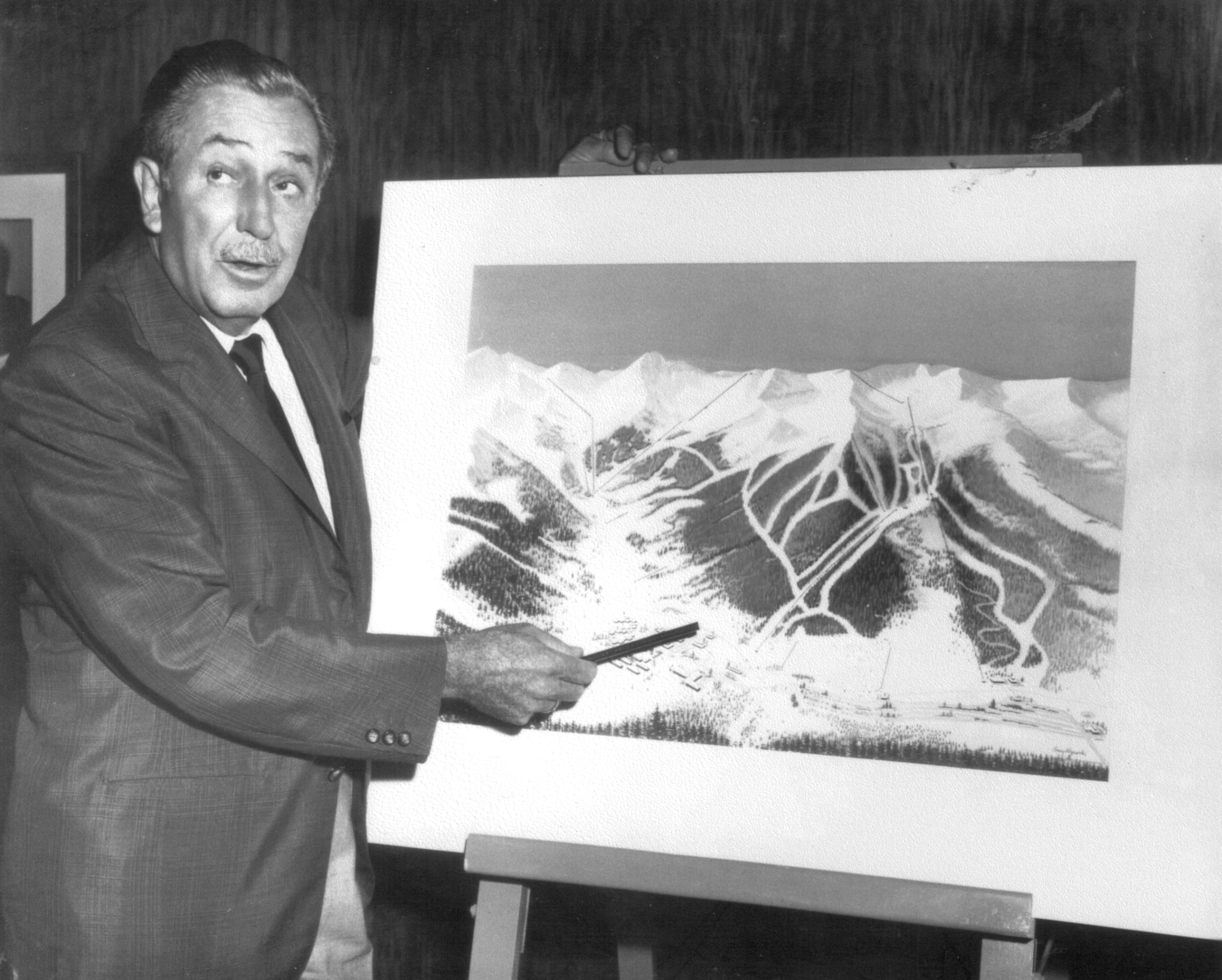

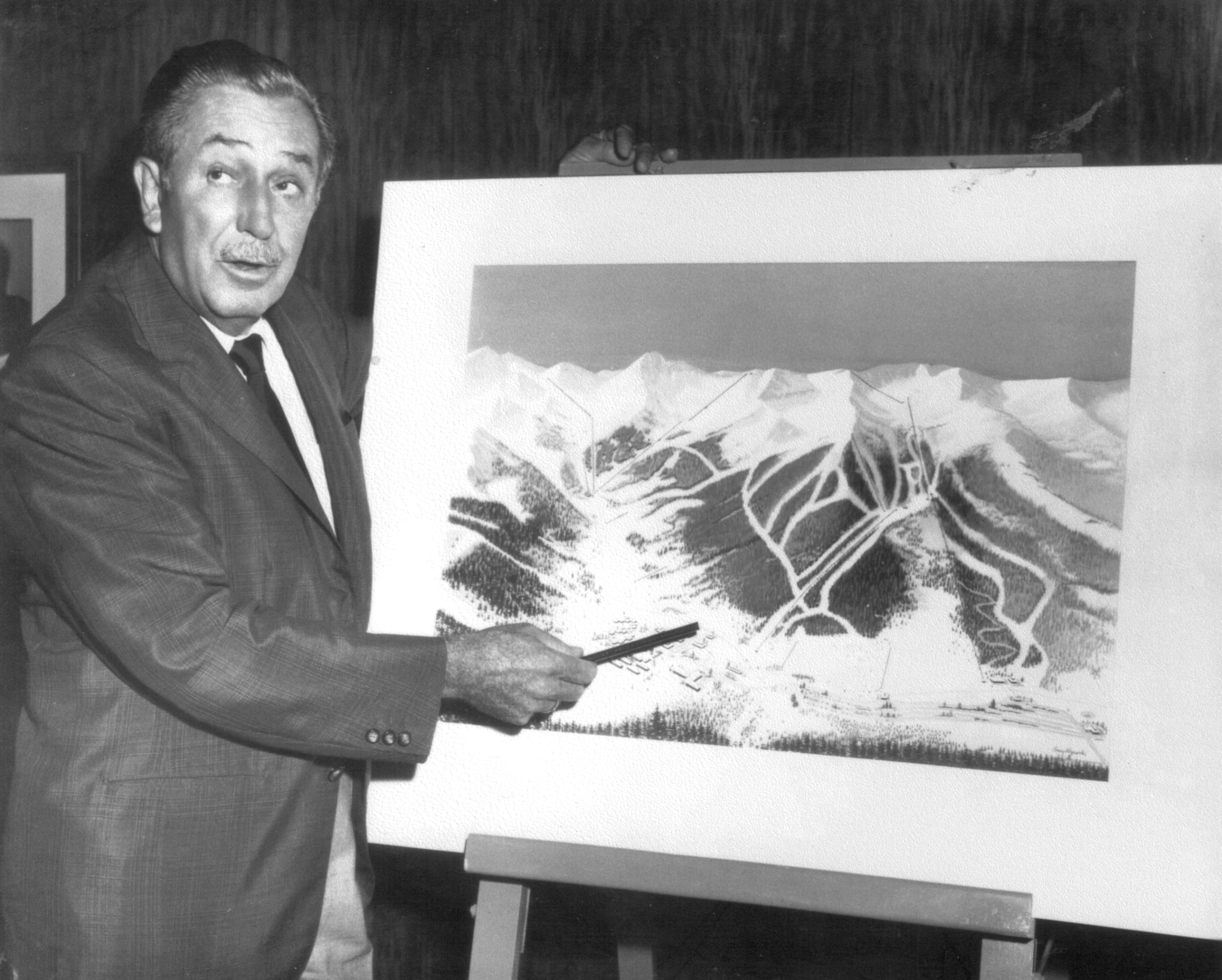

At the time of Walt Disney’s death in 1966, he was leading the charge on building a world-class year-round resort in the Mineral King valley.

Published 20 December 2016, The Kaweah Commonwealth

December 15, 1966, marked an inauspicious event that had major implications for Three Rivers, Mineral King, and, ultimately, Sequoia National Park. On that day, Walt Disney died of lung cancer at the age of 65.

At the time of Disney’s death, he was leading the charge on building a world-class year-round resort in the Mineral King valley. This was going to be the ski resort that showed other ski resorts how it was done. There is no doubt that if this project would have been completed, the Winter Olympics would have been held here.

The Disney proposal eventually pitted environmentalists against developers and, in Three Rivers, neighbor against neighbor. Some residents believed the valley was best left in its current state and others envisioned the dollars that would be pumped into town by the millions of visitors heading up the mountain as well as the winter recreational opportunities that would be just an hour away via state highway.

The U.S. Forest Service, the federal agency that had jurisdiction over what was until 1978 the Mineral King National Game Refuge, was backing the Disney plan. Plans for the ski resort included a new 26-mile, all-weather state highway built from Three Rivers to Mineral King, accommodating 2.5 million visitors annually.

The proposal included a behemoth parking structure, up to 10 stories high, a few miles below the valley that would accommodate 3,600 vehicles. Visitors would access the resort and its two dozen ski lifts spanning 13,000 acres via a tramway.

The year-round “Alpine Village” in Mineral King, nicknamed “Disneyland East,” would consist of two hotels with more than 1,000 rooms, dozens of shops, movie theatre, chapel, conference center, a dozen restaurants, ice-skating rink, and heliport, all in a space smaller than Yosemite Valley but providing an estimated 2,500 jobs.

It was back in 1949 that the U.S. Forest Service first issued a prospectus for a ski development with the blessing of the Sierra Club. But it was the lack of a highway to the area that left this project without any bidders.

That is, until Walt Disney first visited Mineral King in 1960. As of 1963, he had begun quietly yet determinedly moving forward on bringing the business of skiing to Mineral King. He hired experts to poke, prod, peruse, and even purchase the islands of private land in the Mineral King area. Over the next two years, nearly 30 acres had been purchased from 18 contingents.

In 1965, upon a request from the County of Tulare, an amendment to the California Legislature’s omnibus highway bill provided a $25 million grant to improve the Mineral King Road. This opened the floodgates, and bidders began vying for the project. The name Disney carried much clout, and in December 1965, he was the selected to be the developer of a $35 million ski resort in Mineral King (in contrast, Disneyland cost about one-third of that price). He now had three years to complete a plan.

Immediately, the snow surveys began. After all, snow was what was needed for a successful ski resort. But it was snow that also led to the demise of the Disney dream.

In September, just three months before his death, Walt Disney held a major press conference in Mineral King on a cold, blustery day. Governor Pat Brown was in attendance, among other dignitaries.

After Disney died on December 15, 1966, Walt Disney Productions, under the direction of Walt’s brother, Roy, doubled down and continued to push forward with the project.

The ongoing snow surveys required that mountaineers reside in the valley during the winter months. The winters of 1966 through 1969 consisted of heavy snow in the Sierra and flooding of the Kaweah River in Three Rivers on multiple occasions.

On February 23, 1969, three avalanches struck the Mineral King valley from all sides — Empire Mountain, Miner’s Ridge, and Potato Patch Ridge, the steep, west-facing slope that towers over the pack station and East Mineral King area. It was the latter avalanche that slammed into the Mineral King Store and the resort cabins where two ski mountaineers, Wally Ballenger and Randy Kletka were housed. Tragically, Kletka, 26, was killed.

The battle for conservation vs. development in Mineral King was fought all the way to the Supreme Court. The Sierra Club, which had initially been in favor of the project, was the plaintiff in the case against the federal government. Ironically, Walt Disney was an honorary life member of the Sierra Club, bestowed with that distinction in 1955 in recognition of Disney’s nature films.

The Sierra Club ultimately lost the case, but the State of California also withdrew its funding for the highway, so the proposal simmered. (There is so much more to this court battle and highway sage that will have to be saved for a future article.)

Down in Three Rivers, there continued to be two factions, for and against the proposed development. Three Rivers had been without a newspaper since 1956 when, in 1972, Jack and Virginia Albee moved to town and founded the Sequoia Sentinel.

The couple was outspoken in their support of the development in Mineral King. As late as August 1976, they published a two-part article submitted by Robert Hicks, a Disney agent for the Mineral King land purchases. The front-page, above-the-fold, headline exclaimed “Disney dream can still be reality …Says Men who should know!” the first week and “Mineral King Myths” the next, disputing a whopping 47 “myths.”

Here is the editor’s note summarizing the article:

The following material on Mineral King was furnished to ‘The Sentinel’ by Robert Hicks of ‘WED Enterprises’ [the private family holding company of Walt Disney] with the cooperation of the Far West Ski Association. It is a factual update of the whole proposal clearly indicating that Disney interests still, to use the venacular [sic], ARE ‘hot to trot’. In short, they would welcome any changes in both Washington, D.C. and Sacramento that would bring about realization of the fascinating dream of the late Walt Disney, who had such a personal viable interest in the whole affair.

These articles were a last-ditch effort to garner public support for the development after it was proposed that Mineral King become a part of Sequoia National Park. In 1978, the legislation introduced by Congressman John Krebs to add Mineral King to Sequoia National Park was signed by President Jimmy Carter. The matter of a ski resort in Mineral King was finally settled more than a decade after Walt Disney’s death.

While this was not to be the end of contention in Mineral King, it forever laid to rest the threat of a major development occurring in this alpine valley.