This is the second installment of a four-part series that explores a small portion of the embellished lore associated with the creation of Sequoia National Park, exposing little-known aspects perhaps suitable only for the Halloween season and those with sturdy digestive systems. In Part 1, we met Will Trauger, who was plummeting down a mineshaft, and James Wolverton, a legendary man whose life concluded just as the Park’s began. This week, we join some Boy Scouts on a search for James Wolverton’s grave.

By Laile Di Silvestro, 7 October 2019, 3RNews

The rattlesnakes were still dormant on the first day of March in 1936. Seven boys were walking on the hillside above the East Fork of the Kaweah River. They rustled through the stalks of last year’s grasses still towering above new green growth, and they inhaled the overpowering smell of buckthorn blossoms. The boys were seeking a spot on the ground under which the bones of a hero lay.

They were seeking the grave of Lieutenant James Wolverton. With the Second World War looming overseas, honoring the resting place of the local Civil War icon made for a meaningful outing. The boys were members of Troop 23 led by Lloyd Fletcher, a local landscape architect whose work is now on the National Register of Historic Places.

The nature and timing of the boys’ adventure was no accident. The troop was sponsored by the Big Tree American Legion Post – the same big tree purportedly named General Sherman by James Wolverton. Frank Been, Sequoia National Park’s first full-time ranger-naturalist led the outing. At the same time, Sequoia National Park was preparing to host a Boy Scout camp at Wolverton Meadow. Well-publicized resurrection of Wolverton as a symbolic hero made sense.

The story of James Wolverton and his naming of the General Sherman tree emerged as early as 1914 in newspaper articles promoting Sequoia and General Grant National Parks. By 1935, Wolverton’s tale had fully evolved, and numerous newspapers published large front-page articles featuring the hero. With his journalistic exhumation, Wolverton’s reputation grew. Wolverton had now become an acquaintance of John Muir, and he was patrolling the Park at the time of his death. Most articles ended by wondering why James Wolverton chose to be buried in an isolated grave.

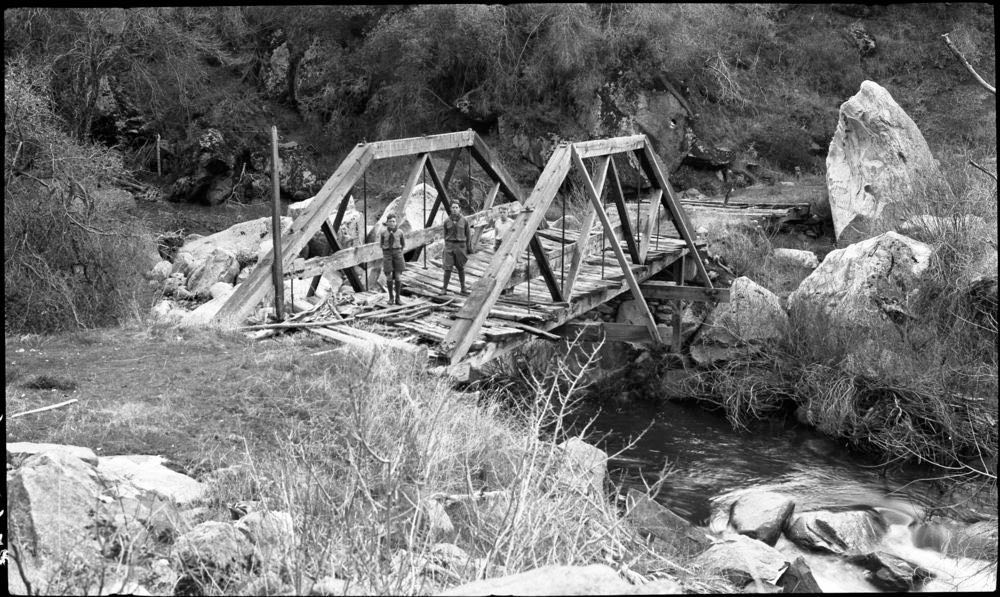

According to local lore, Wolverton’s grave was near a wooden bridge built in 1879 to carry miners and supplies to the Mineral King mines and silver ore back down. There, in in October 1893, Wolverton supposedly received a dignified burial with the military honors suitable for a Civil War lieutenant who had served under General Sherman. In 1936, the bridge was still standing, but the road was no longer in use. Fire had swept through, consuming any grave markers in its path, and new vegetation had obscured any telltale mound or depression. James Wolverton’s gravesite needed rediscovery.

Jim Barton, 95, of Three Rivers was eleven years old on that day. He remembers walking the abandoned Mineral King Road down to the East Fork of the Kaweah River and the rickety wooden bridge that crossed it. According to contemporary newspaper reports, the boys found a site distinguished by a large moss-covered bolder. Two weeks later, they returned with new wooden head and foot markers and built a trail to the site.

Given the passage of more than four decades and at least one brush fire, however, is it certain the boys found the exact location of the grave? How would the troop definitively recognize the gravesite? When reminiscing in 2002, Jim Barton expressed some uncertainty.

“I don’t think we found it,” he noted before reminding his listeners of the effect time wields on memories.

Compounding the doubt is another mystery. There are no census, voting, or property records for a James Wolverton in Tulare County between 1874 and 1893.

Regardless, two things are now nearly certain. Forty-three years before young Jim Barton sought the grave, and a decade before plummeting down a forty-foot shaft, Will Trauger’s boots compressed the soil under the Boy Scouts’ feet. And somewhere in the vicinity lies a six-foot skeleton exhibiting the ravages of what could well have been venereal disease.

In the next installment, we follow the path of a man named Joel Rivers Woolverton to his ghastly end.

2 thoughts on “J. Wolverton and the Ghastly End 2”

Comments are closed.