A History of the Kaweah Colony: Resignation, Suicide, and Dispute

By Jay O’Connell. This 3RNews version as published August 2020.

I have my belly full of “co-operation” and the “labor movement” at last, you bet. (Burnette G. Haskell, November 1891)

The summer of 1891 was vastly different for the Kaweah Colony than the summer only one year before. The previous year, with their road complete and real hope that their land claims would be resolved favorably, it looked as if the Kaweah Colony would join that short list of successful American cooperative communities. Even during a troubled winter, hope remained alive. Annie Haskell opened 1891 with the following entry in her diary:

Another year has dawned. How they do roll away—one after the other, and yet it seems a long time since last New Year. Last New Year I caroused, this one I did not. I returned in time from “the hall” to welcome it in my own house, under my own roof. There is something in that. If Burnette had only been here. When I woke I found a little bird fluttering about. How it got in I don’t know, but it surely came to bring us a message of good luck and happiness.

But soon she was complaining about the increasing bickering and tensions within a community struggling to survive. “This whole colony is full of people who can’t mind their own business,” Annie wrote in her diary. She was tired of people sticking their noses into “something that doesn’t concern them,” and lamented that her husband, Burnette, got “nothing but kicks for his pains and it makes me crazy.”

After it became increasingly apparent that the Colony’s efforts at Atwell’s Mill were a dismal failure, Haskell had taken about as many kicks as he could stand.

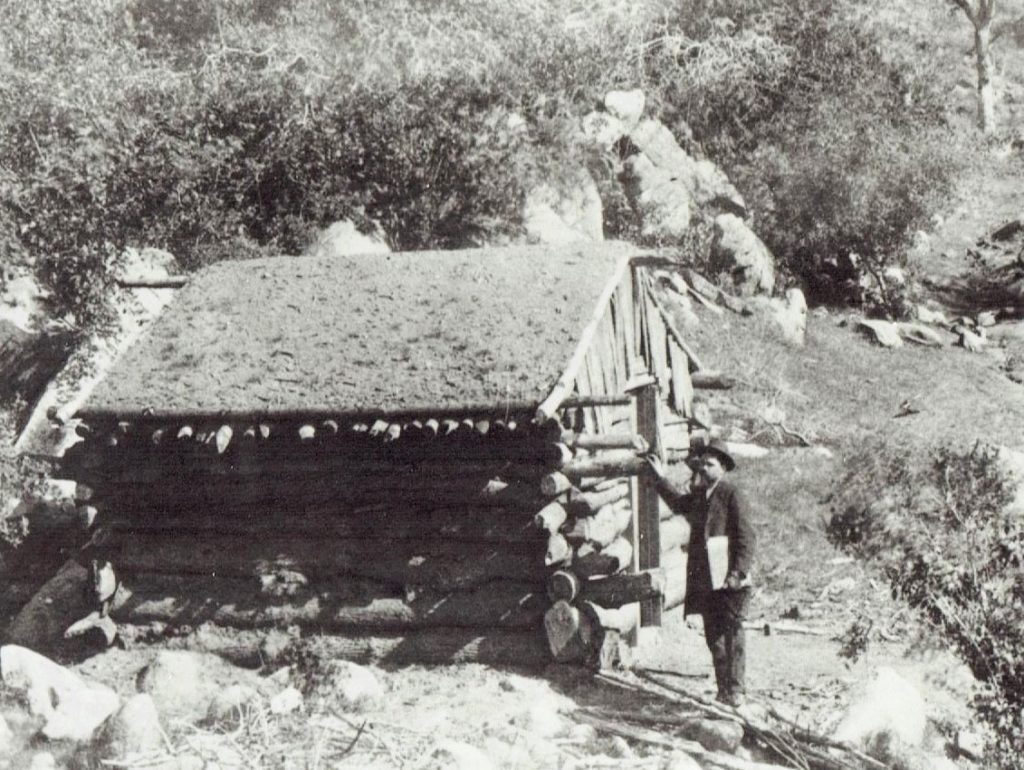

FAILURE AT ATWELL’S MILL

It should be pointed out that while Captain Dorst’s interference certainly had a debilitating effect on Colony logging, their Atwell’s Mill operation was probably doomed from the start. The equipment, some of which was included in the lease from Atwell’s heirs, was in poor shape. And the leased land surrounding the mill was already nearly logged out. Most of the useable pines and firs were gone, and the colonists had to resort to cutting giant sequoias, a labor-intensive undertaking that produced much wasted lumber. And finally there was the condition of the road, which always has rendered any large-scale operation in the Mineral King area economically impractical.

Burnette Haskell summed up why he felt Atwell’s Mill failed in his article, “How Kaweah Fell,” written in November 1891:

The Trustees issued to the resident members an imploring circular, urging the workers to more active and persistent effort at the mill. But this appeal had no permanent effect except to arouse antagonism. Work still continued in the same desultory fashion until the last of July, when Taylor was sent up to the mill. While there he discovered that the force had, with the carelessness of children, cut over their line on to government land, thus again exposing the Trustees to arrest and prison.

The strength of any organization lies in the people involved, and through cooperation, many hoped the whole (the Kaweah Colony) would exceed the sum total of the parts (the members). No one had preached this more fervently than Burnette Haskell, who had always possessed great talent to motivate. In the circular urging members to work harder, Haskell wrote, “Individual selfishness now means inevitably the ruin of Kaweah. Do you want to live or die?”

Haskell claimed that after five months, the operation at Atwell’s Mill cut only one-tenth of the 2.5 million feet they had expected, and “instead of being produced for $10 [per thousand feet] or less, it had cost from $18 to $20, and it was sold for $10.” Haskell added that “comment is superfluous, and whatever excuses may be made, the business failure is flat.”

HASKELL RESIGNS

The run of bad luck and the failure of the sum total to live up to expectations had, by the summer of 1891, left Haskell disillusioned. On July 25, Haskell, along with trustees Horace T. Taylor and William Christie, tendered their resignations from the Board of Directors. Notice was published in The Kaweah Commonwealth. The departing trustees, with forced graciousness, proclaimed:

In our time of trial and trouble, the new blood and brain and energy of Barnard and Purdy and others have sprung to the front, able to lead us out. We salute and retire to the ranks. There let us stand shoulder to shoulder in the fight and give them loyal support.

As the year progressed, there was much fighting but it certainly wasn’t “shoulder to shoulder.” Early in August, Annie noted in her diary:

Burnette has resigned… and I was very glad of it. I wish he had never seen, heard, nor dreamed of this colony—but then we would never know what a mistake cooperation is.

The Kaweah Commonwealth naturally did its best to put as positive a slant as possible on the news of the resignations, stating that it should not be looked upon by anybody as “being an evidence of any dissatisfaction with Kaweah.” The paper claimed that Haskell, along with Taylor and Christie, had given up their office “solely and simply because they know they can do better work in the ranks.”

But why did Burnette Haskell, who had worked so hard and tirelessly on behalf of his cooperative dream, finally resign his position? One clue can be found in Haskell’s resignation letter to the Board as legal counsel for the Colony:

I herewith tender my resignation as the Attorney of this company. This resignation is made because I am firmly and finally convinced that my services are not appreciated.

Of course, it was more than a lack of appreciation that prompted Haskell’s actions. We have already seen that he felt operations at Atwell’s Mill were grossly mismanaged and that workers had carelessly exposed the trustees to possible arrest by cutting trees beyond the lease boundaries. On closer examination of his resignation letter, we see another root of Haskell’s anger, and perhaps the root of much of the growing Colony discord.

In June, 1886, the Colony was formed [Haskell wrote] and I have transacted its legal business ever since without ever having received a single cent of cash or single credit on the books for such services. I have never charged you a fee although I have never volunteered my services gratuitously. But I esteem it equitable that you should pay me for my time at the same rate at least that you paid for pick and shovel work on the grounds; and that such payment should be in cash as I received no subsistence from Kaweah Colony. I enclosed you therefore my bill to date.

It may seem ironic that money had become such a motivating factor for Haskell. But the socialist agitator had never preached against the evils of money per se, but against the “competitive system” and “Capitalist scheme where Justice and Fraternity are sacrificed to the spirit of selfish greed.” Justice and Fraternity were now being pushed aside by self-preservation throughout the Kaweah Colony.

Haskell, the idealist, had also become frustrated by what he perceived as sloppy bookkeeping. He had become a realist, sensing that the light at the end of the tunnel was an oncoming train. In his resignation letter he offered the following warning:

In resigning, I desire to again call your attention to the absolute necessity of observing your by-laws exactly, and especially of entering every financial transaction of the Company on the books. As your Attorney, I know that half of your most important affairs are not upon your books and I again warn you that in case a suit for dissolution should be brought, and this is liable to happen at any time, your Secretary [James Martin] and indeed the whole Board, would be placed in a difficult and dangerous position. The folly of continually postponing and neglecting the accounts of the Company is an invitation to criminal process in the hands of any disgruntled member and an actual ever-present danger which has no excuse whatever for being.

It doesn’t take a lawyer to see that this warning also contains a thinly veiled threat by Haskell, perhaps the most disgruntled of any member at the time.

One other factor that undoubtedly raised Haskell’s ire that summer was once described by Tulare County historian Joe Doctor:

Old man [Elphick] came to the Colony at the age of 80 after years of selling newspapers at Lotta Fountain in San Francisco. He invested his little savings in the colony with the assurance that he would be well taken care of to his dying day. It wasn’t long coming. He reached the colony after a long hot ride by train and stage from San Francisco. It was July, and the day after his arrival the temperature soared to plus 100 degrees. Eager to be of assistance, the old man went out to work in the field of string beans and about noon he fell dead between the rows. There was an inquest but no cause of death established. Haskell told in his journal that he had suffered the most ignominious insult of all—that of being accused of doing the old man in for his money.

The San Francisco Chronicle reported, with headlines reading “Elphick’s Death—Rumors of Foul Play Freely Circulated,” that the frugal old man had gone to Kaweah to see about recovering $800 he had allegedly loaned the Colony and had died mysteriously. Members of the Colony, disturbed by the rumors, signed and sent a petition to Haskell requesting that he clear up several questions raised by the old man’s untimely death, including what happened to Elphick’s money. Even though charges were never formally made, and the San Francisco Examiner later reported that Elphick was clearly not the victim of foul play, the implications had to have been crystal clear to Haskell.

Frustrated at the disorganization of the Colony, feeling unappreciated and uncompensated, and finally accused — even if only an implied accusation — of murder, Haskell resigned one other post that summer. From The Kaweah Commonwealth, August 8, 1891:

Mr. Haskell, with this issue of the paper, resigns as Superintendent of Education, and, under the by-laws, places the paper in Mr. Martin’s hands as Secretary. He thanks all friends and comrades for the kind support given in the past and entreats its continuance for the future.

SUICIDE AT KAWEAH

In October 1891, exactly one year and a day after moving to Kaweah, Annie Haskell wrote the following account in her diary:

Such a horrible thing. Frank Wigginton was found this morning in bed, with a bullet hole through his brain and a pistol in his hand. The shot was heard at 6:00 a.m. Everyone is horrified. It seems impossible to believe that it is a case of suicide and yet he must have done it himself somehow. Poor boy, he was the best of all the young fellows down there [Kaweah]. Everyone liked him. The news has made me sick.

The Kaweah Commonwealth reported that the deceased was a “native of Ohio, about 27 years of age, and a resident of Kaweah for about one year.” The newspaper also noted his “cheerful, kindly disposition with not a trace of moroseness in his nature.” The Commonwealth further explained:

The coroner of Tulare County was summoned and upon his arrival an inquest was held. Not the slightest part of the testimony showed that he had deliberately contemplated suicide, on the contrary, all the testimony went to show that he was happy and contented and satisfied with life, and that he had made arrangements to build himself a permanent home here.

The Visalia papers offered slightly different accounts of the tragedy and even hinted at a possible motive for the young man’s suicide. The Tulare County Times described the event in rather graphic detail, noting that Wigginton was found “still in bed, the pistol grasped firmly in his right hand lying on his breast, while immediately between and a little above the eyes a gaping bleeding wound showed where the leaden messenger had sped on its deadly work.” The paper also noted that Wigginton was universally liked by associates and of a cheerful disposition “although of late he has complained of what he believed the unjust treatment of himself and his associates by the government.” It is interesting to note that the Tulare County Times was still very supportive of the Colony at this time, while the Visalia Delta, which had become vituperative in its attacks on the Colony, offered a significantly different account of Wigginton’s state of mind:

A few days ago [Wigginton] was hauling some wood, and he made the remark that that was the last load he would ever haul. Wigginton had spoken frequently of going away from the colony to earn enough money to build a house for the winter.

It is perhaps reading too much between the lines to claim that the Delta infers Wigginton’s suicide was motivated by financial duress brought upon by a failing Colony, but when reporting an earlier suicide connected with Kaweah, blame is very clearly assigned to the Colony. On July 30, 1891, the Visalia Delta printed the following:

Last Saturday’s [San Francisco] Chronicle contained a lengthy article relating how Gus Hodeck, a member of the Kaweah Colony, committed suicide owing to the persecution he had endured while at Kaweah. He joined the colony about two years ago, and because he had an opinion of his own regarding the management of the colony, and dared express it, he incurred the enmity of the so-called board of trustees. A mock trial was held and Hodeck was expelled from the colony, losing all the money he had paid in as membership fees. Thoroughly disheartened with his treatment, Hodeck returned to San Francisco, hoping to find work as a machinist in the Union iron works. Not meeting with success, he hired a room last Thursday, turned on a gas jet and suffered the death of asphyxiation. The Chronicle, in its opening paragraph, said “Driven to death by the Kaweah Colony” ought to have been the verdict of the Coroner’s jury upon the remains of Gus Hodeck.

While the Delta could rationalize the obvious slanted bias of this report by labeling it the Chronicle’s account, it does mark a turning point in their reporting of the Colony, and foreshadows George Stewart’s devastating series of exposés that appeared later that year.

TING’S BITING LETTER

The Delta had, since the inception of the Kaweah Colony, reported with a remarkable restraint of judgment. It was particularly noteworthy that during its agitation to create a national park reserve, Stewart and the Delta were supportive of the Colony’s claim to land in and around Giant Forest. But as 1891 progressed, the paper became decidedly less positive in its comments concerning the Colony, and in November published a four-part history and scathing exposé on the Kaweah Co-Operative Colony.

The vehemence with which Stewart now attacked the Colony might seem an abrupt about-face, but Stewart had been exposed to definite and mounting motivations. In October, he received a letter from former colonist Peter Ting, which may have prompted, or at least confirmed, Stewart’s negative feelings for the Colony. Having heard that the Delta was willing to publish “true statements regarding the Kaweah Colony,” Ting was pleased to offer a “few facts.”

He prefaced his remarks by stating that he thought the best thing a local county newspaper could do would be to “expose such fraud and save families from being ruined by such vile creatures as the old Trustees of the Kaweah Colony.” Ting called the last two years of Colony existence “nothing more than a confidence game” and criticized Haskell’s despotic control of the so-called democratic process.

Ting put the question of the land claims into perspective when he wrote:

In order to shield themselves from being blamed for deceiving the people at first in regard to the title of the land, they now make the plea that the Government is persecuting them and trying to take the Colony’s land away, when in fact the Colony has never had any land and would have had but very few claims even if the individuals had got their land, for who would want to turn their claims over to the Colony when it is run by such men as Haskell, Redstone and Martin?

One major theme of Stewart’s series was that bickering and in-fighting had crippled the utopian enterprise. It had become a prevalent and apt criticism. By the time of Wigginton’s death in October 1891, members of the Colony were arguing and fighting over just about everything. Annie Haskell offered one particularly disturbing example in her diary the day after Wigginton’s death:

We all went down to attend the funeral. It is very sad. After Burnette made all the arrangements and appointed the time for the funeral, then the Redstone outfit came over and took charge of things and hurried the funeral away two hours before the time.

THE SWEET POTATO WAR

One episode that illustrates the depths to which the Colony had sunk — the bickering and fighting, the hardship and desperation — involved nothing more than a few sweet potatoes. Annie Haskell’s diary offers a version of the incident:

A gang of fourteen men came up to Green’s place and began to dig, sack and haul away his sweet potatoes. They knocked him down, choked and mistreated the old man very badly. Owen and Burnette were there and interfered somewhat. They said they were coming here this p.m. to get the cow but they did not. Burnette has been guarding the place all p.m. with a rifle.

In an affidavit he prepared with Haskell’s help, Albert W. Green, age 58 years, explained that in the event of his death, the affidavit could be used posthumously. Even though his injuries were, as stated, severe, he thought however that he would survive. Annie Haskell, commenting on his injuries in her diary, noted that Green seemed “to be hurt internally and is considerably bruised and can’t sit up in bed without being lifted.”

In his affidavit, Green explained his membership in the Colony and the agreement he had made with the trustees to exchange produce for lumber and help in improving his land. He claimed the land was “waste ground that he worked hard—10 to 18 hours a day—to produce corn, squash, pumpkins and potatoes that he turned over to the Colony. They ate it up but did no improvement on my place in return.”19

The Visalia Delta reported on the incident:

On November 5th a number of the colonists repaired to the potato field and commenced to dig the spuds. Old man Green was incensed with the proceeding and made a feeble resistance. He stood on the potato sacks and he testified that he was thrown to the ground, hit on the body, choked and generally ill-treated.

An explanation as to why these sweet potatoes came into dispute was offered by the Tulare County Times:

There are two factions now in Kaweah, the minority headed by Burnette G. Haskell; the majority adhering to J.J. Martin. Among other property of the colony is a garden, which has been under the care of Mr. Green, one of the Haskell faction. In this garden was a patch of sweet potatoes, claimed as colony property, but to which Green set up an individual claim.

In Green’s account, it was Haskell’s intervention that kept the mob, led by John Redstone, J.C. Weybright, Phil Winser, and Irvin Barnard, from beating him to death. He claims Haskell exchanged words, keeping his hand in a pocket in which “presumably he had a gun.”

If we are unclear at this point as to what really happened, an account by Phil Winser from the December 5, 1891, Commonwealth (which was now under James Martin’s control) should only add to the confusion. After stating the reasons why the potatoes were actually Colony property, the issue of the physical assault was addressed. Winser wrote:

We found Mr. Green, Mr. Haskell and Mr. Owen standing there, and the former became very excited and tried to stop us from digging by standing over the tools. He did this to Mr. Redstone and was quietly and gently pushed away by him. This was the extent of “Uncle John’s” assault on Mr. Green, although one or two others removed him with rather more force, though doing him no bodily injury.

As also is another story that Mr. Green would have been murdered had it not been for Mr. Haskell and his revolver. It is true Mr. Haskell called us to witness that Mr. Green was being murdered, but the revolver did not appear, and everyone was too well aware of the harmless nature of our intention on Mr. Green’s person to witness anything of the kind.

History certainly teaches us that there is always more than one side to any story. The Tulare County Times, one of the few outside newspapers that still supported the failing Colony and the Martin faction, addressed what they called a “trumped up” assault charge, writing:

Behind this was an ulterior motive. Saturday a general meeting of the colony was held. The Haskell faction desired to control the meeting and run everything their own way; to do this it was necessary to get a large number of the other side out of the way and so reduce the majority. If enough of these could be arrested and removed upon some charge, however flimsy, then Haskell would have control. The potato episode seemed to furnish the means to this end.

What really happened? We can only speculate. Except for Annie Haskell’s testimony in her diary about Green’s injuries, one could easily suspect Haskell of just such a ruse. A Visalia court, however, found Weybright guilty of assault and fined him $25. It seems most likely this dispute was symptomatic of a growing sense of panic in Kaweah. When things were running smoothly, cooperation had seemed to work. But as the end drew near and even food was scarce, cooperation disintegrated under the strain of tough times — when cooperation was needed the most.

COLONY DEATH RATTLE

By the end of 1891, Haskell had become desperate for money and sold an article to the San Francisco Examiner entitled “How Kaweah Failed.” The brilliant propagandist, once so tireless in his efforts to promote the Colony, was now driving the final nails into the coffin. Haskell, of course, was not the only one disillusioned with the Colony, nor was he the only one writing critically of the endeavor.

George Stewart’s series of articles in the Visalia Delta came out about the same time as Haskell’s Examiner piece. Both focused on the internal squabbles as one source of the Colony’s downfall, but whereas Stewart pointed the finger of blame at the founders and leaders of the Colony, Haskell blamed the weakness of human nature. Stewart harshly criticized the misleading nature of Colony propaganda while Haskell railed against a capitalist conspiracy. Stewart noted the comparative luxury in which Colony Secretary James Martin lived while other colonists were reportedly near starvation; Haskell bemoaned the existence of “too many average men.”

Shortly after Stewart’s scathing series appeared, Haskell, Martin, and H.T. Taylor were arrested for “using the mails for fraudulent purposes in sending out literature to people stating that the Colony owned thousands of acres of timber land.” So dispersed was the Colony by this time that only three of the five trustees named in the indictment could be arrested, as the other two had already left the Colony.

Indeed, by this time — January 1892 — the Kaweah Co-Operative Colony Company, having failed to “weather the storms of internal disintegration,” had been dissolved. In its place had sprung the short-lived Industrial Co-Operative Union of Kaweah, with James Martin as president. But it was too late for any phoenix to rise from the Colony’s ashes. Split into irreparable schism and denied their only resource (timber), the Colony’s reformation was in fact nothing more than its final death rattle.

The March/April 1892 issue of The Kaweah Commonwealth printed the official minutes of the Kaweah Colony for 1892, stating that on April 9, the 50th General Meeting of the K.C.C.Co was “adjourned sine die, there being no quorum present.” This was the last issue of The Kaweah Commonwealth published by the Colony — a Colony which, in any form, had ceased operation. A bitter Haskell later wrote:

A few more than half of the resident members at the November meeting, 1891, abolished the time checks, took possession of the machinery and land of the colony, repudiated the credits of the old workers, and decided to continue the struggle as a small enterprise under the absolute power of one man. It is needless to say now that this attempt was as well a failure. They hoped to make a living here as small farmers thus cooperating. Whether this plan would have succeeded cuts no figure whatever with this history. We can leave them quarreling over the little property left, as we leave coyotes quarreling over a carcass.

SOURCES: A handwritten draft of a circular, “A Serious Word to the Members,” signed by B.G. Haskell and H.T. Taylor, dated July 7, 1891 (Haskell Family Papers, Bancroft Library) provided primary source information for this chapter, as did many of the already oft-cited contemporary news reports; diaries of Annie Haskell; and Haskell’s Out West account. A few other interesting sources include an undated petition to Haskell and A.W. Green to “furnish an explanation of the actions and conduct in relation to the late Father Elphick,” signed by, among others, James Martin, Irvin Barnard, Phil Winser, and George Purdy (Bancroft Library); a handwritten note from Albert Green to the Tulare County District Attorney dated November 11, 1891, found included in a letter Haskell wrote to his father (Haskell Family Papers, Bancroft Library); and a letter to the editor by Peter Ting to the Visalia Delta, dated October 25, 1891 (handwritten copy, Kaweah Colony collection, Visalia Public Library).