A History of the Kaweah Colony: Incident at Atwell’s Mill

By Jay O’Connell. This 3RNews version as published August 2020.

The reign of the Cossack they thought was in Russia, not America; but they had yet much to learn about our capitalist-owned land of the free and the home of the brave. (James J. Martin, ‘History of the Kaweah Colony’)

Even with Secretary Noble’s adverse decision and the conviction of the trustees for illegally cutting timber, the leaders of the Kaweah Colony refused to give up. By late spring they had, however, decided not to continue cutting at the mill site at the end of their road. As the Commonwealth noted on May 28, 1891, the trustees had decided that “it was best not to cut any more lumber on our claims until the civil cases are decided; and this decision cannot be had until September.” The paper went on to explain that to continue cutting would surely provoke “more arrests and persecutions from the Trust using the machinery of the Government.” But that course of inaction left the Colony without any source of income except payments of outside members, which Haskell realized were being adversely affected by what he called “the Associated Press slanders telegraphed throughout the country.”

With nearly 200 people living at the Colony that needed basic supplies and an urgent need for lumber to build homes at the new Kaweah Townsite, the Colony had a pressing need to investigate all their options. They learned that there were 320 acres of fine timber land — also located within the boundaries of the newly created Sequoia National Park, but which had been patented years before to Judge A.J. Atwell — on which a fully equipped mill had been operated in the past. For two years it had not been run on account of the death of the owner, and the estate was currently in probate. As the Commonwealth reported under the headline “Joyful News,” Irvin Barnard managed to obtain a lease “on exceptionally favorable terms the land, mill machinery, etc., complete!”

The inhabitants of this county [the reporter continued] will have their cheap lumber after all; we shall have work and food; and money to fight our cases in Court for our own lands and print and publish a million copies of the history of the outrages we have been subjected to.

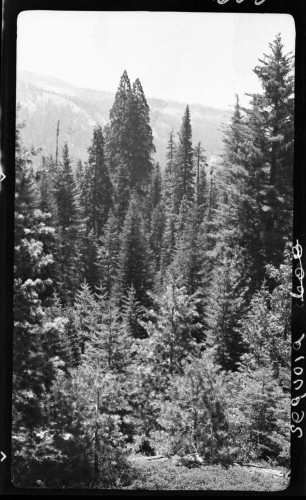

Atwell’s Mill was located over 20 miles from Kaweah, on the already existing road to the high alpine valley of Mineral King, which had experienced a brief mining boom in the 1870s. By 1891, the area was beginning to flourish as a summer mountain resort destination. While Mineral King itself was not within the park boundaries, its proximity to national park lands and the already established road and resort status made it a natural choice as the site for the temporary headquarters for the first administrators of Sequoia National Park. When the Kaweah colonists made the decision and arrangements to relocate their lumbering operations to Atwell’s Mill — privately owned land that was within the park boundaries — they were well aware of whose path they would inevitably cross.

CAVALRY TO OVERSEE PARK

In January 1891, newspapers reported that Secretary of Interior Noble had “requested the Secretary of War to station a company of cavalry in the Sequoia National Park and in Yosemite to prevent depredations on the mammoth tree groves.” The Visalia Delta, in an editorial, admitted that “just what their duties will be is not yet known, but they will be required to prevent the destruction of the forest, killing of game, etc.”

Earlier reports had pinpointed one specific threat, “the so-called Bellamy colonists, who have in part perfected a title to the lands on which these trees stand, and have expressed their purpose to hold their claims in spite of all opposition. Another threat were the “hoofed locusts,” as grazing sheep herds were sometimes called. The newly created parks encompassed many summer grazing lands of valley ranchers, much of which were on patented and privately owned land.

The Delta noted that “the Secretary of the Interior has a knotty problem on his hands. He cannot prevent people from occupying their own lands, nor is it reasonable to suppose that they will be prevented from passing to and from the same. What is to be done with these isolated fragments remains to be determined.” One such isolated fragment was Atwell’s Mill, which the Kaweah Colony had leased. This dilemma of dealing with privately owned land within the park boundaries has been a recurring and ever-present one and is still being debated today.

The first person who had to deal with this knotty problem in Sequoia National Park was Captain J.H. Dorst. The Visalia Delta reported that Captain Dorst, “commanding Troop K of the 4th U.S. Cavalry, who has been selected to take charge of the Sequoia National Park, arrived in Visalia and the following day departed for the mountains to select a temporary camping place for his command.” The April 16, 1891, issue of the Delta continued, “Different places were examined but the spot that appeared to be most suitable is on the Mineral King road,” at a place known as Red Hill.

As pointed out in Lary M. Dilsaver and William Tweed’s book, Challenge of the Big Trees, Dorst’s first task was “to locate the new Sequoia National Park, and the tiny General Grant National Park as well, and develop plans for policing the tracts.” As the first military superintendent of the state’s first national park, Captain Dorst found himself blazing new procedural trails. “He soon discovered,” Dilsaver and Tweed wrote, “that two roads entered Sequoia — the 1879 wagon road to Mineral King and the recently built Colony Mill road… ending at the now closed mill.” Dorst decided to base his operation in Mineral King, even though the new park did not include the Mineral King valley, because most people entering the park would probably do so via that route. From their temporary camp at Red Hill on the lower stretches of the road, “Dorst sent troops to assist the county in repairing winter damage to the roadway. On June 7, he entered Mineral King valley, although the melting snowpack prevented establishment of a permanent camp there until June 29.

As the Commonwealth reported on May 23, 1891, Dorst’s troops “passed up the canyon on the other side of the main river Sunday. They did not stop at Kaweah.” The paper also noted that even though the Cavalry “has not yet entered the canyon of the North Fork, nor made its appearance at the Colony pinery,” the trustees had already made their decision not to cut any more lumber at the Colony Mill.

This did not mean, however, that the Cavalry and the Colony would not meet. “As the Cavalry did not come to us,” the Commonwealth pointed out, “we have gone to them!”

DISCONCERTING NEIGHBORS

As everyone knows, there is always more than one side to any story. Several sources can be used in trying to reconstruct what happened at Atwell’s Mill when the Colony began lumbering operations and the United States Cavalry tried to stop them. These include “The Atwell Mill Outrage,” from James J. Martin’s unpublished “History of the Kaweah Colony”; personal letters of Burnette G. Haskell; “Memories,” the unpublished memoirs of Phil Winser, who worked at Atwell’s Mill; and “Cutting Timber at Atwell’s Mill,” a special report to the Secretary of the Interior by Captain J.H. Dorst.

Remembering back to the incident some 40 years later, James Martin’s ire was easily raised. He recalled that he thought “the reign of the Cossack was in Russia, not America; but [we] had yet much to learn about our capitalist-owned land of the free.” Explaining how Irvin Barnard had leased the land and that George Purdy was foreman, Martin pointed out:

They were both veterans, and had fought to preserve the Union. Their patriotic blood boiled when the troops came and ordered them to stop cutting where there was no shadow of doubt as to their rights. Foreman Purdy is reported as saying: “And so this is the Union I fought to preserve; troops are now used to harass law-abiding settlers. No, by the Eternal, I’ll not stop! I am in my rights here and doing my duty. The country is not at war, and if I am to be stopped it shall be through civil process, not military.”

Irvin Barnard had acquired the lease on Atwell’s Mill on May 20, 1891, which, unlike the Colony Mill, was in close proximity to giant sequoia trees. First owned by Isham Mullenix during the end of the Mineral King mining rush, it was sold to A.J. Atwell in 1885. Because of its remote location, the mill was never profitable. When the Colony acquired it, the county road accessing it was in bad condition and the mill had long lain idle, “but the need for lumber was urgent, and this was the best the situation offered.”

Mineral King, which had become headquarters of Captain Dorst and his Cavalry Troop K, was only a few miles farther up the road from Atwell’s Mill. The Colony and the Cavalry were now neighbors, and Dorst was well aware of the Colony’s presence at, and plans for, Atwell’s Mill.

As early as May 25, Dorst had written to one official asking for specific instructions in connection with his duty in charge of the park. He well anticipated difficulties and mentioned the Atwell sawmill, saying that “arrangements are now being made to commence works at that mill. I shall warn the owners that I cannot allow any timber, big or little, to be cut down, and that I have written for information about the matter.”

Dorst then received further instruction from Special Land Agent Andrew Cauldwell, who had already become quite a thorn in the collective side of the colonists. He told Dorst there was no objection letting the old logs lying about the mill be sawed up, “as they had been cut down some time before the park was established, and were an eyesore anyhow, but pending definite instructions he thought that no timber should be cut.”

On June 19, 1891, Dorst was riding by the sawmill and noticed that two or three pine or fir trees had been felled. “I inquired for the man in charge,” Dorst recounted, “and was referred to Mr. Purdy. He declined to stop the timber cutting without being restrained by the order of a civil court, and [stated] that he was not under military government.”

DORST’S DILEMMA

Captain Dorst’s first difficulty concerning the cutting of lumber at Atwell’s Mill was determining just what the official government policy was. Agent Cauldwell, it has been noted, had told Dorst that he should allow no lumber to be cut. A few days later, Dorst learned that Cauldwell had received a telegram, dated June 16, from the acting Secretary of the Interior, directing him to suspend action in the case of Atwell’s Mill until the Secretary, who was on summer vacation, could be contacted.

With this knowledge, obtained at Cauldwell’s Visalia office while the Land Agent was away in Yosemite, Dorst headed back to his camp via the Visalia to Three Rivers stage. “Mr. Barnard was one of the passengers,” Dorst recalled. “He spoke to me of my visit to the mill and asked me about it. I told him of the telegram to Mr. Cauldwell and that there would probably be no interference with his cutting timber.” Though both men were probably hopeful that the issue would somehow blow over and resolve itself, they undoubtedly knew better.

Finally, in early July 1891, Dorst received the long-delayed response to his initial request for clarification on the issue. From the Acting Secretary came this reply:

I approve of your action in regard to the saw-mill, but you will communicate with [Land Agent] Cauldwell, now near you, and report if you have any difficulty in the premises. You will prevent, by all means, the destruction of any of these great trees within the lines of your reservation.

As this mentioned only the Big Trees — giant sequoias — Dorst felt that “the claim might be made that it should be construed to mean them only.” None had been cut as yet, and so on July 6, he sent the following telegram to the Secretary:

Letter received. On June 19 found several pines or firs cut down at Atwell’s mill. Parties refused to stop without orders of civil court. Afterwards was telegram to Mr. Cauldwell, dated 16th, directing suspension of action, case of Atwell’s mill, pending your decision, and have done nothing since. Pines and firs still being cut, but no redwoods. Is this permitted; letter mentions redwoods only?

On July 13, Dorst received the following reply at his camp:

Washington, D.C. July 9, 1891— You will not permit the cutting of any timber within the park until further orders. Chandler, Acting Secretary.

That afternoon, Dorst sent a copy of this telegram to Irvin Barnard, along with a letter stating, “I have the honor to request, therefore, that you will cause the cutting of timber to be discontinued on the tract of land… which you have leased, or claim to control, for I am informed that all that land lies within the limits of the park.” The letter was directed back to Kaweah and into the hands of the Colony legal counsel, Burnette Haskell.

Haskell promptly sent his directions to Barnard. “Do not stop cutting except upon the actual threatening of armed force and the presence of troops sufficient to carry out the threat. Be dignified, cool, respectful, but determined.”

A confrontation was inevitable. Phil Winser, remembering back some 40 years later, recalled the confrontation with “a troop commander with little judgment.” As Winser remembered:

[Dorst’s] instructions were to stop all timber cutting in the Park and he interpreted that to mean us. A small detachment was sent up our road and made camp two or three miles further on; soldiers would be sent out on foot to run down predatory sheep men and a cavalry man on foot in such unknown mountains with the light air of those elevations certainly had a tough time.

I remember coming in from work one evening and seeing two of them stagger into camp at the last limit of endurance. Of course, we fed and rested them and the boys at the bunk house, knowing we might be interfered with, would fill them up with wild stories of what a terrible lot we were and our local reputation as reds and a bunch of “anarchists” helped the effect.

So one morning as Jim and I were putting in an undercut, who should ride up but a lieutenant and three or four troopers. He halted and said “You will stop cutting this timber.” We said nothing and kept chopping; then he got off his horse, came up to me and repeated the order, laying his hand on me, with the same result, so he remounted, hesitated a bit and said, “Well, I’ll go and get men enough so you will stop.”

THE WINCHESTER BLUFF

Captain Dorst continued the story from his point of view. “A corporal reported that one or two more trees had been cut at the mill, and I ordered Lieutenant Nolan with ten or eleven men to go up and stop any further cutting.”

By this time, Dorst well knew with whom he was dealing and had concluded that the leaders were looking for an opportunity to claim persecution “and to use the sympathy it would excite to make the public blind to any defects in their claim to the Giant Forest, as well as gain recruits.”

Dorst’s keen assessment was confirmed by James Martin himself, who later wrote that “the attorneys for the colony were hoping the act of restraint by force would actually take place, so that a basis for bringing the case before the Court could be established.”

Lieutenant Nolan was dispatched to execute, if necessary, this restraint by force. He and Dorst had “talked a good deal about what should be done in case the people at the mill compelled us to act against them.” Dorst advised against the exercise of absolute force “except in the last extremity.” When Nolan arrived at the mill, about 30 men appeared and he was told he would be resisted. Phil Winser’s account details this encounter from the colonists’ point of view:

Pretty soon [the] lieutenant and about ten troopers jingled up and ordered the cutting to cease, the only result being the crash of a nearby tree or two; no reply being made at any time. He must have been an amiable man, reluctant to push things to extremes, a hot-headed one could have made trouble. Ours was straight bluff and the reputed Winchesters hidden in the brush were sheer figments of imagination.

Dorst’s side of the story noted that one of the colonists, “a deputy sheriff by the name of Bellah, told [Lt. Nolan] that he would consider an interference with work as a breach of the peace, and would arrest anyone who attempted it.” Dorst also mentioned that “none of the mill force had arms, at least in sight, but most had axes.”

After Nolan’s encounter, Dorst made the trip up from Red Hill camp. Along the road he met Barnard, who was headed to Visalia to have warrants issued for Nolan’s arrest. They discussed just what would constitute an act of restraint by force. Barnard replied that “laying hands on his men while cutting trees and taking them away would be his idea of force.” Barnard was hopeful that any application of force would be done in a manner as to leave no doubt, in a legal sense, of being defined as such. Dorst was simply eager to resolve the situation.

I reached Nolan’s camp [Dorst wrote], about a half mile from the mill, shortly before midnight. I had been ailing for several days, and had a fever then, and did not feel competent to engage in any business where tact, good judgment, and clearness of mind were necessary. I sent a note to Mr. Purdy, intending to go to the mill after the fever subsided. It kept up and, unwilling to delay any longer, sent Lieutenant Nolan to the mill with two men to find out just how much force they wanted me to use.

The Lieutenant agreed to carry out this plan without further delay. Deputy Sheriff Bellah, whose official sense of duty seems to have been whatever Mr. Barnard dictated, stated that he would not interfere. Accordingly, several men took axes and commenced cutting. By order of the lieutenant, one soldier advanced to one of the men who was cutting, placed his hand on him and ordered him to stop. The man replied “I won’t” and kept on cutting.

After a number of like responses, Nolan decided not to press the matter any further and returned to camp and reported to Dorst. Shortly afterward, Purdy came to Dorst’s camp and stated that “all work had been stopped until Mr. Barnard’s return.” Perhaps the rather histrionic show of physical restraint had some effect after all, although the colonists would never admit as much. Purdy had explained that it was not because of the army’s orders, but that the “events of the past two or three days had caused a good deal of excitement, so much so that [the men] would not work steadily but at every opportunity break up into groups and commence talking.” They were simply too agitated to get any work done.

The next day Dorst received a copy of a telegram recently sent to Cauldwell:

Washington, July 24, 1891— It appears that Atwell’s mill is on patented land. If this is correct instruct Captain Dorst to defer action on all patented land until I can communicate with Secretary. George Chandler, Acting Secretary.

Dorst sent a copy of this telegram to Barnard along with a note stating “In compliance with the foregoing, you are respectfully notified that you will not be interfered with by me in your work at the mill.”

SOURCES: Supplementing the contemporary news reports from The Kaweah Commonwealth, Tulare County Times, and the Visalia Weekly Delta, books such as John Muir’s Our National Parks; Challenge of the Big Trees by Dilsaver and Tweed; and John F. Elliott’s Mineral King Historic District: Contextual History and Description (Mineral King Preservation Society, 1993) served as valuable source material. Firsthand accounts of the incident at Atwell’s Mill were found in Captain J.H. Dorst’s Special Report to the Secretary of the Interior Relative to Cutting Timber at Atwell’s Mill, September 8, 1891 (Sequoia National Park archives); Phil Winser’s “Memories” manuscript; a letter from Burnette Haskell to J.J. Martin, Irvin Barnard, H. Dillon, July 15, 1891 (Haskell Family Papers, Bancroft Library); and James Martin’s unpublished “History of the Kaweah Colony.”