During the 1918 H1N1 influenza pandemic, Three Rivers opted to handle matters in its own way.

By Sarah Elliott and Laile Di Silvestro, 16 April 2020, 3RNews

The global influenza outbreak of 1918 ranked as one of the deadliest epidemics in history. The so-called “Spanish flu” claimed more lives than World War I, which ended the same year the pandemic struck. In fact, more U.S. soldiers died from the 1918 flu than were killed in battle during the war. The virus infected an estimated 500 million people worldwide — about one-third of the planet’s population at the time — and killed up to 50 million victims. United States casualties numbered 675,000.

The Spanish flu reached its height in autumn 1918 and continued until 1920. Why the name “Spanish” flu? Because news of the flu came mostly from Spain, a neutral country in the war and, therefore, not subject to wartime censorship rules that bound other countries.

The 1918 flu was first observed in Europe, the United States, and parts of Asia before swiftly spreading around the world. The flu’s spread was in large part due to troop movement around the world as a result of the war.

The 1918 flu was first observed in Europe, the United States, and parts of Asia before swiftly spreading around the world. The flu’s spread was in large part due to troop movement around the world as a result of the war.

At the time, there were no effective drugs or vaccines to treat this killer flu strain. Citizens were ordered to wear masks; schools, theatres, and businesses were shuttered; and bodies piled up in makeshift morgues before the virus ended its deadly global reign of terror.

In the United States, victims ranged from residents of major cities to those of the most remote Alaskan communities. President Woodrow Wilson reportedly contracted the flu in early 1919 while negotiating the Treaty of Versailles, which ended World War I.

There were tight restrictions on U.S. citizens. People in San Francisco were fined $5 (about $85 in today’s dollars) if they were caught in public without masks.

Here is a roundup of local newspaper articles, accompanying commentary, and added contextual tidbits regarding the flu’s effect on Thee Rivers.

It was the autumn of 1918 and the denizens of Three Rivers had been visiting friends and family despite the risk of spreading or catching the deadly H1N1 influenza virus that was circulating the globe. In the towns and cities elsewhere around Tulare and Fresno counties, schools had closed and there was a “cessation of public activities and gatherings.”

Three Rivers opted to handle the epidemic its own way despite evidence of the flu’s impact as close to home as Visalia. Three Rivers residents assuredly read the newspapers, and were aware of both the increasing number of cases and the actions being taken to control its spread.

The front page of the October 19 edition of the Visalia Daily Times focused on both the final stand of the Germans in Word War 1 and the flu. Visalia schools were already closed, and there was a quarantine in effect. The sheriff and undersheriff had caught it, as had a physician. A court case was delayed because the plaintiff was ill.

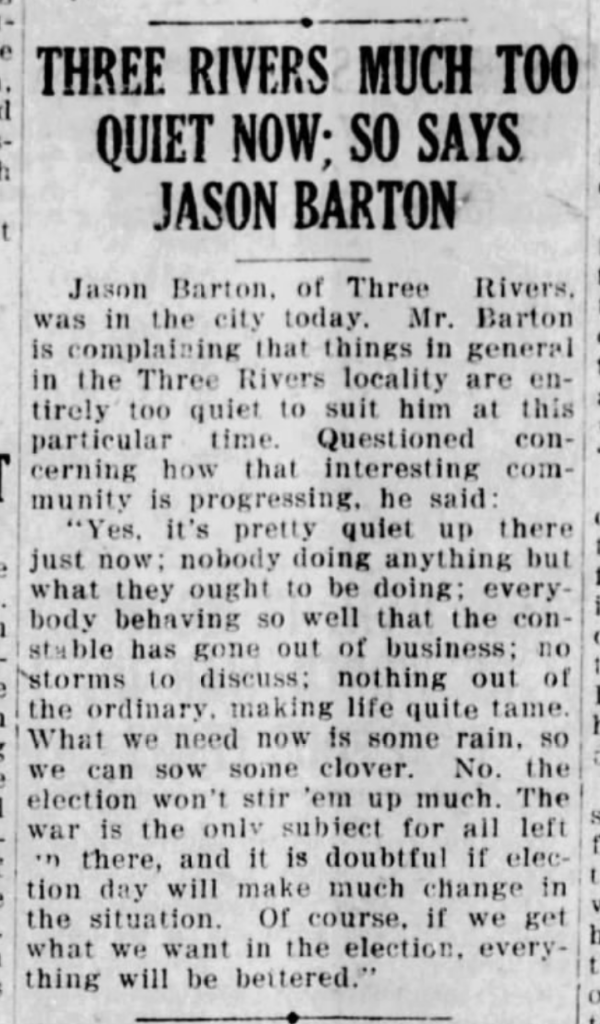

Perhaps most notably, however, Jason Barton declared Three Rivers much too quiet.

“Yes, it is pretty quiet up there just now,” he noted. “Nobody doing anything but what they ought to be doing; everybody behaving so well that the constable has gone out of business; no storms to discuss; nothing out of the ordinary, making life quite tame.”

October eased into November, and Three Rivers residents continued to behave as if the pandemic-mitigating rules and guidelines didn’t apply to them.

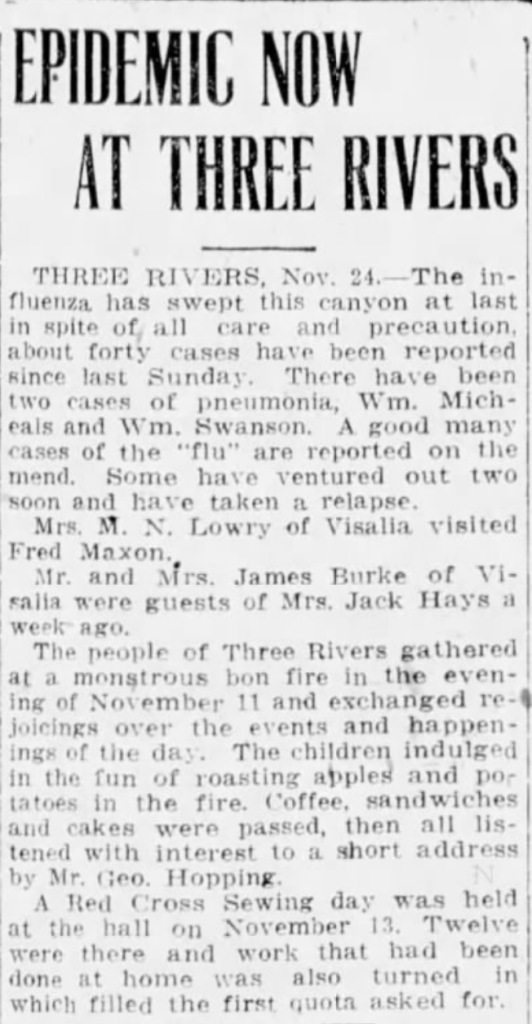

The news reported the notable gatherings. Fred Maxon hosted a woman from Visalia and Mrs. Jack Hays hosted the Burkes from Visalia. It is quite possible the virus arrived with the guests.

On November 11, the entire community gathered to celebrate the armistice that ended fighting on land, sea, and air between the Allies and Germany. They built a large bonfire, “exchanged rejoicings” and passed around apples, potatoes, coffee, sandwiches, and cakes. And, of course, the influenza virus.

On November 13, twelve women got together for the Red Cross Sewing Day. At that point, if any one of them were not already in the early stages of illness, she would likely have caught it at the event.

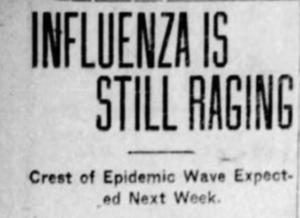

By the 24th, the flu had Three Rivers in its grip. About 40 cases had been reported over the course of a week, and William Micheals and William Swanson were struggling with secondary pneumonia.

Jason Barton’s town was no longer too tame.

At the end of November, the flu had not abated, but people were increasingly concerned about impact the closures and quarantines were having on the local economy and students.

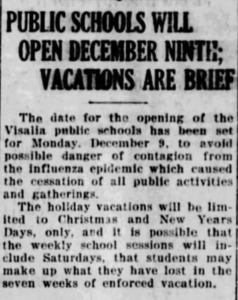

The Visalia public schools were planning to reopen December 9 after what would have been seven weeks of closure. The schools had been closed as part of the “cessation of public activities and gatherings” put into effect to mitigate “the possible danger of contagion from the influenza epidemic.”

Given the reports of new flu cases in other articles on the same page of the newspaper, one might wonder if reopening the schools wasn’t premature.

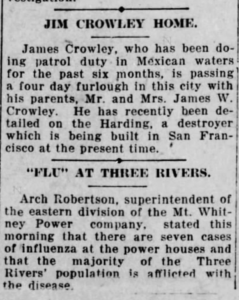

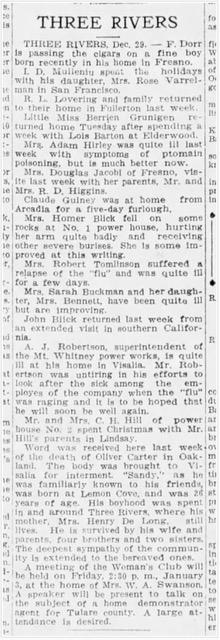

Take Three Rivers, for example. The amazing Archibald “Arch” J. Robertson (1879-1932) of the Mt. Whitney Power Company reported seven employees at the three power houses were ill with the flu and stated that the majority of Three Rivers residents were afflicted.

In other news, the 18th Amendment prohibition hadn’t yet gone into effect, but breweries were closed down as a result of the temporary Wartime Prohibition Act, which banned the sale of alcoholic beverages having an alcohol content of greater than 1.28%. And Jim Crowley (ancestral relative of one of the authors) came home. Like many young men returning from war assignments at the time, he may have been carrying the flu along with his joy.

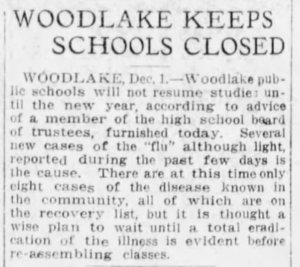

In stark contrast to Three Rivers and other communities, nearby Woodlake opted to take a cautious approach.

On December 1st, Woodlake decided to keep its schools closed until the new year, at the earliest, deeming it wise to “wait until a total eradication of the illness is evident.”

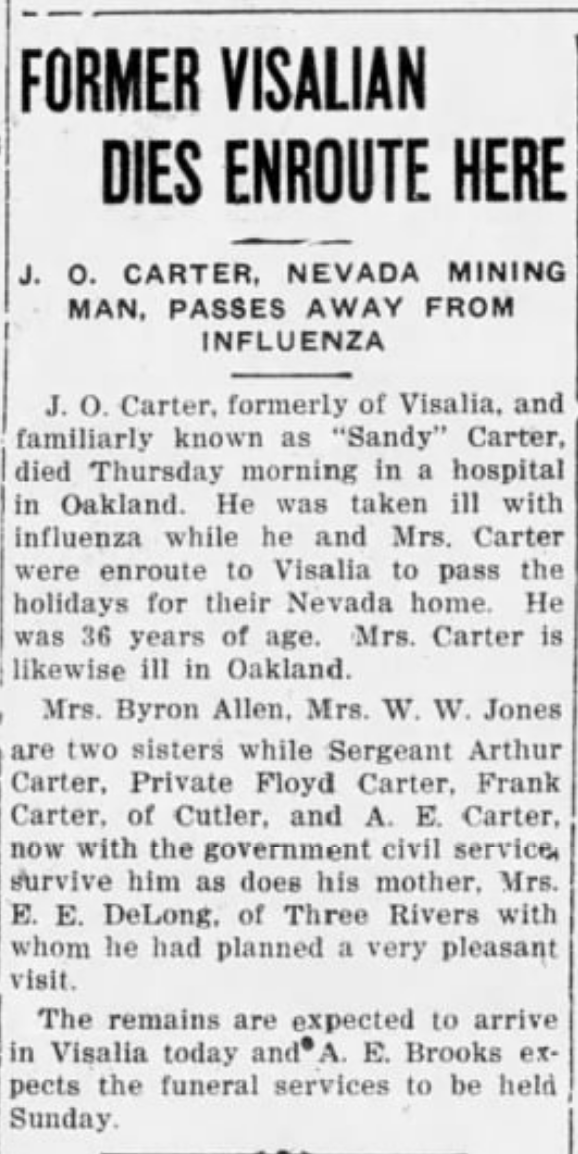

By the third week of December, the influenza struck close to home.

Joseph Oliver “Sandy” Carter died while he and his wife were on their way to visit his mother in Three Rivers for the holidays. Sandy was a well-known Three Rivers lad with strong Mineral King connections. Unlike COVID-19, the 1918 influenza tended to hit the youth the hardest. Sandy was only 35.

The flu didn’t take a holiday break. And neither, it seems, did the Three Rivers social scene.

The news reported considerable comings and goings, gatherings and visits. The virus, of course, hitched a ride.

The flu continued to impact the women in Three Rivers. On the 29th of December, three women in Three Rivers were quite ill with the flu. Despite this, the Three Rivers Woman’s Club decided to meet at the Swanson home, and encouraged “a large attendance.”

Despite the severity of their illnesses, Barbara Lee Tomlinson (1887-1977) and the other women survived the flu.

Meanwhile Arch Robertson, the Mt Whitney Power Works superintendent whom we met in the November 30 article, had been exerting “untiring” efforts to tend to his sick employees in the Three Rivers power houses. Perhaps others were trying to help, as well, including Mrs. Blick, who fell on some rocks at one of the power houses. Arch Robinson managed to stay well throughout most of the month, but fell ill himself just as the others were well on the path to full recovery. He and all his employees survived.

As 1919 rang in, newspapers were still full of death and illness notices.

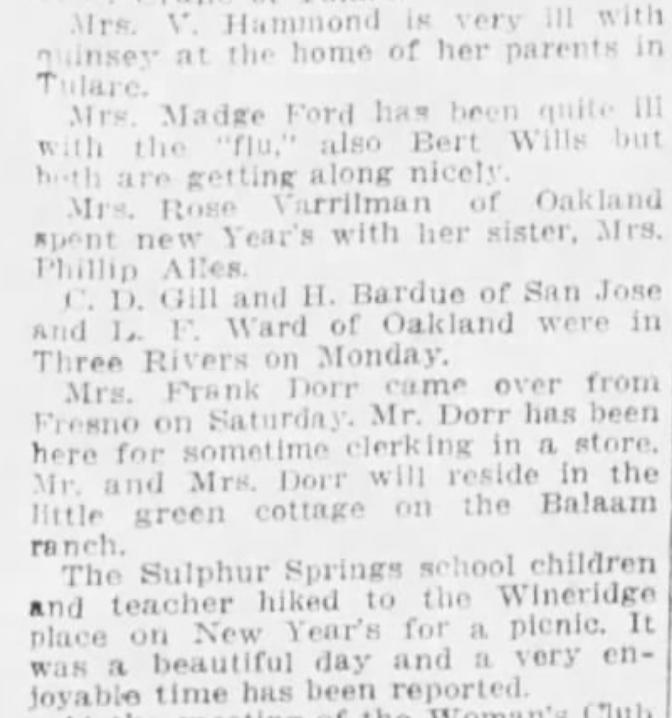

In Three Rivers the first week of the new year brought two more case. In addition to Bert Wills, Mrs. Madge Ford was ill with the flu. One can’t help but wonder if she didn’t get it at the Women’s Club meeting.

Mrs. V. Hammond had a bad case of tonsillitis, which was perhaps a post-flu secondary infection.

People continued to travel and socialize in close proximity, and school remained in session. The Sulphur Springs School students took a hike to Wineridge for a picnic.

By the second week of January, the consequences of keeping the Three Rivers schools open became evident.

Miss Eugenia “Minnie” Irwin (1868-), a Three Rivers teacher was “quite ill with influenza.” Rather than closing the schools at last, Three Rivers opted to hire Charlotte “Lottie” H. Goad (1885-1976) to take Minnie’s place. Minnie recovered and lived for at least six more years.

Given that a substantial percentage of the Three Rivers population contracted influenza, it is perhaps difficult to understand the town’s cavalier attitude compared to that of other communities. Perhaps the attitude derived from the fact that no one had actually died in Three Rivers. Yet.

Meanwhile, the community eagerly anticipated the upcoming wedding of Henry Canfield and Ida Berg…

Miss Ida Berg and Mr. Henry Canfield of Three Rivers were married on January 5, 1919.

We can imagine the celebration. The hugs. The dances. The kisses. The sharing of food and drink.

Within a few days, Ida was ill.

On January 13, she was dead.

Ida was one of the last of the Three Rivers residents to catch the flu, but first to die. Indeed, the records suggest she may have been the only one to die.

Perhaps due to its lack of precautions, Three Rivers suffered a high rate of contagion compared to other towns in the region. Its mortality rate was much lower than the 2.5% estimated rate for the “Spanish” flu worldwide, however.

May we continue to be so lucky.