A History of the Kaweah Colony: Stewart and the Land Office

By Jay O’Connell. This 3RNews version as published August 2020.

Plans were matured with little delay, and on October 5, 1885, thirty-seven persons appeared at the United States Land Office in Visalia to make application to enter tracts of this land under the Timber and Stone Law (Act of 1878). (George W. Stewart)

When Charles Keller, on his train trip back through the San Joaquin Valley, learned of available timber land, he immediately set out to investigate the matter further. To find out more, he even enlisted the help of the first Euro-American man to ever see the giant sequoias of what was already being called the Giant Forest. But first Keller headed to the Land Office in Visalia to confirm what he had heard and acquire maps and surveys of the available forest land. Having checked his information, Keller set out to see for himself all he had heard about the Giant Forest.

To that end [Keller wrote in 1921], I interested two neighbors, who agreed to go with me provided I furnished the outfit. Lenny Rockwell, one of those who agreed to go with me, had at one time lived at Three Rivers, and thus was acquainted with the Tharp family.

Rockwell’s wife is credited with having named the tiny village of Three Rivers, so christened in the 1870s because it was situated at the convergence of three forks of the Kaweah River, in the hills on the edge of the mighty Sierra. The Kaweah River actually consists of five forks that drain one of the steepest watersheds in all the Sierra. Those forks are the North, Middle, Marble, East, and South. In the 30 or so miles from its headwaters to the floor of the San Joaquin Valley, the Middle Fork of the Kaweah River drops an impressive 12,000 feet, passing through several biological zones and through a wide variation in topography and vegetation on its swift downward journey.

At a broad widening of the Kaweah canyon just below Three Rivers (on land that is today under the Lake Kaweah reservoir) was the homestead and ranch of Hale Tharp, one of the area’s earliest settlers. Tharp’s knowledge of the forest that Keller was setting out to explore was unsurpassed by any local settlers as he had visited the forest before any other Euro-American.

THARP AND THE GIANT FOREST

Hale Tharp had come to Tulare County in 1856, settling on the Kaweah River at the edge of the Southern Sierra foothills some 20 miles east of Visalia. Tharp had befriended the local Native American chief, Chappo, who in turn showed Tharp the magnificent giant sequoia forests and lush meadows of the adjacent mountains.

I had two objects in making this trip [Tharp recalled]. One was for the purpose of locating a high summer range for my stock, and the other was due to the fact that the stories the Indians had told me of the “Big Trees” forest had caused me to wonder, so I decided to go and see.

Since 1861, Tharp had used the area known as the Giant Forest for summer pastures and had even secured patents on some of the land that had been entered as swamp and overflow land — lush meadows that provided ample summer grazing for his stock. On the edge of one meadow, Tharp built a cabin from a single fallen sequoia tree that fire had hollowed.

When famed naturalist John Muir visited the spectacular forest in 1876, his exploration included a chance meeting with Hale Tharp, who extended his hospitality to the wandering student of nature. Muir explained to the stockman that he had come south from Yosemite and was only looking at the Big Trees. At Tharp’s spacious single log cabin, Muir enjoyed a fine rest and nourishment while he listened to the “observations on trees, animals, adventures, etc.” of the “good Samaritan” Tharp.

Muir later took credit for giving the forest its name when he wrote that “after a general exploration of the Kaweah basin, this part of the sequoia belt seemed to me the finest.” He decided to call it “the Giant Forest” and described it as “a magnificent growth of giants grouped in pure temple groves, ranged in colonnades along the sides of meadow, or scattered among the other trees, [extending] from the granite headlands overlooking the hot foothills and plains of the San Joaquin back to within a few miles of the old glacier fountains at an elevation of 5,000 to 8,400 feet above the sea.”

Charles Keller obtained permission to use Tharp’s fallen-log cabin as a base of operation and was told he could count on Tharp’s son, Nort, as a guide once he reached the mountain forest. The forest was everything Keller had heard and more. During the summer of 1885, Keller was able to make his own surveys of the area and familiarize himself with the lay of the land.

With his own plats and surveys of the available and heavily timbered land, he sent a report to James Martin in San Francisco, who was secretary of the Land Purchase and Colonization Association. It was the duty of every member to consider themselves “a committee of one to seek out opportunities to purchase, and to notify the Secretary of such finds.” Keller, with a sense of urgency, suggested Martin call a meeting, read his report to the members, and ask as many as possible to come to Visalia to view the land and each enter claims for a quarter section of prime forest land. Martin later recalled that “the association thought Mr. Keller’s vision excellent.” With the Kaweah canyon as an available colony site and the timber as an abundant resource, along with ample water power at hand from the river, Martin realized that “with an eye for the practical,” they were indeed “visionaries.”

A BUSY LAND OFFICE

Keller’s report to the association in San Francisco “received immediate acceptance,” and he was notified to expect “upon a certain day, 40 of our members” to meet him at his home in Traver.

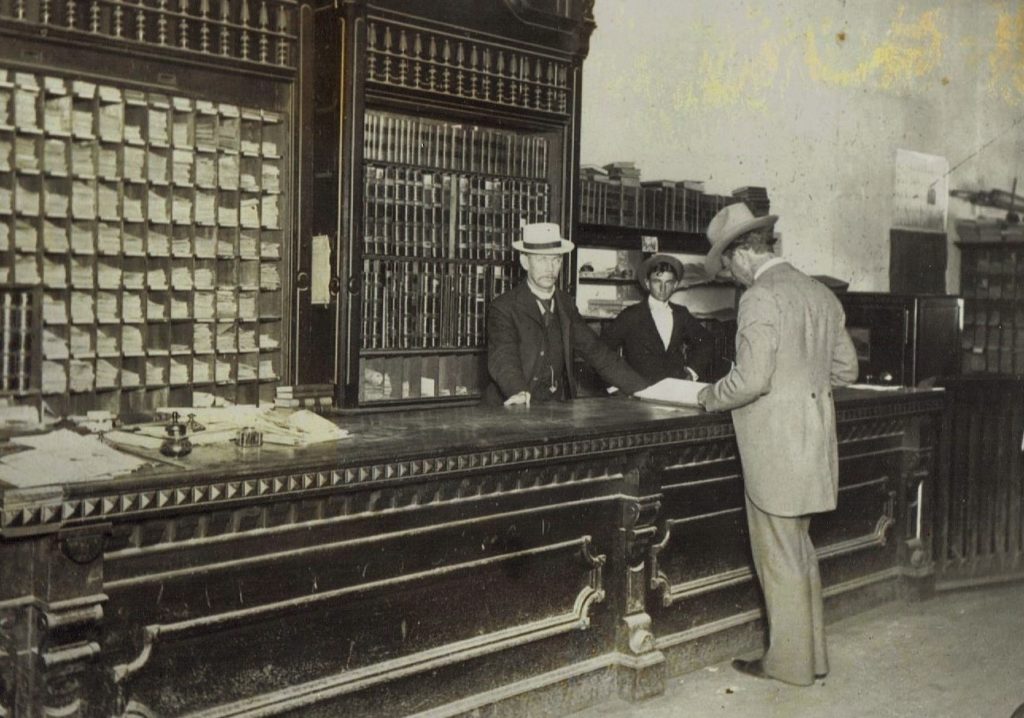

In October 1885, the General Land Office in Visalia became a busy place. Visalia was far from being a sleepy little farm town. The county seat of Tulare — a county that had tripled in population during the 1880s — Visalia was also the oldest town between Stockton and Los Angeles. A certain amount of activity and 19th-century hustle and bustle was to be expected, but the activities in the Land Office that October were well beyond the range of normal.

On October 5 of that year, 37 men, including Land Purchase Association founder Burnette Haskell, showed up at the Land Office. Each made an entry to purchase 160 acres of timber land at $2.50 per acre, available under the Timber and Stone Act of 1878. It must have been quite a sight as these men, dusty and ragged from their journey down from San Francisco, descended on the Land Office, crowding into the room and filling it with the noise and excitement of their enthusiasm. The registrar must have felt like a harried sales clerk at a candy store, besieged by dozens of clamoring children. (Another group filed on October 30, 1885, bringing the total number of filers to 53.) Keller, of course, had become “uniquely conversant with the necessary endeavoring” (as he once phrased it) to legally secure government land and so made sure all the rules were carefully followed.

The first rule stated that filers of government land were required to have examined the land they sought to purchase. Keller claimed, in his memoirs, that he organized a “trip of inspection” with each man “sleeping upon the quarter [section] he intended to file on.” This may have been an exaggeration — and although written 35 years after the fact, an exaggeration first uttered in the Land Office in 1885 — as it is hard to imagine being able to lead over 50 filers, most of whom were city-dwellers, into the Sierra forest without benefit of roads or even well-established trails.

Indeed, Keller’s memoirs describe one such trip of inspection, which provides some idea of the difficulties in believing that every single filer slept on his applied-for quarter section of land. After a laboriously slow journey “on a very rough trail under Moro Rock into the forest,” the party arrived at the plateau situated between the Marble and Middle forks of the Kaweah. At the western edge juts Moro Rock, a majestic mass of granite rising hundreds of feet from the forest (and dropping off thousands of feet on the valley side). Keller describes them as being “pretty much spent” by the time they reached the forest with its unsurpassed stands of sequoias covering some 2,500 acres and containing 20,000 mature sequoias.

While the forest also contains various firs, cedars, and pines, it is the concentration of giant sequoias that make the region unique. Native only to the western slope of the Sierra, the massive sequoia’s foliage somewhat resembles the incense cedar. But there the similarity ends. Mature sequoias average 15 feet thick at the base and about 250 feet in height. Exceptional trees exceed 300 feet in height and 30 feet in diameter. In age and stature, the Sequoiadendron giganteum is the unrivaled monarch of the Sierra forest.

Across the canyon of the Marble Fork, with its succession of cascades over marble cliffs, the sequoias thin out and disappear, but there are still vast tracts of pine and fir trees. White fir is dominant here, but also plentiful are incense cedar, ponderosa, Jeffrey pine, Douglas fir, red fir, and the majestic sugar pine. These forested slopes and ridges west of the Marble Fork also comprised the land on which Keller and his associates filed claims, and Keller’s trip of inspection therefore headed in this direction.

It now devolved upon me [Keller explained] to assume sole responsibility to guide the party through a trailless wilderness, to a point where I aimed to connect with the North Fork [of the Kaweah River]. I kept my misgivings to myself, and inspired our party by expatiating upon the grandeur and magnificence of the forest.

Dropping west over the saddle ridge that divided the Marble canyon from that of another of the Kaweah’s five forks, the group made it down the adjoining canyon to the Kaweah’s North Fork. They had to overcome steep descents, shortages of water, thick underbrush, poison oak, pack horses falling off ledges, individuals becoming separated and lost, and a host of other difficulties. They eventually worked their way down to the convergence of the North Fork and a large creek feeding it from the east (today called Yucca Creek, they would name it East Branch), and finally through the narrow foothills canyon of chaparral, oak woodland, and grassland.

Keller noted that “the city people were very much the worse for wear,” but all was well as it ended well. Keller, in later correspondence, reiterated the claim that he “led three different parties to the land, constituting 57 in number,” and so fulfilled the law demanding that all applicants have been on the land they desired to purchase, to which they all had to swear.

That requirement met, each filer had only to pay a $10 filing fee, arrange to publish notices of their claims in a local newspaper, and then return after 60 days and pay $400 for their individual quarter-sections, at which time they would receive legal title to the land.

STEWART AND SHARED SUSPICIONS

George W. Stewart was editor of the Visalia Weekly Delta when, as he later recalled, he was “reading the proofsheets of the notices, [and] detected the fraudulent nature of the applications and called the attention of the Register of the Land Office to the matter.” Looking at the information on those notices today, the only apparent clue that Stewart could have construed as indicating potential fraud was the fact that several of the applicants listed the same San Francisco address — a boarding house on Broadway. More likely, it was the mere circumstances of the mass filing itself, as well as the physical appearance of the filers themselves, that aroused suspicion.

First of all, San Joaquin Valley residents assumed that this land and its timber were inaccessible except through the expenditure of large sums of money, only possible by some giant corporation. There was, thus, a natural tendency to suspect that these were dummy filers, much like the fraudulent claims Keller had helped to uncover in Northern California years earlier. Suspicion was furthered by the fact that the group, on the very day of the filing, met at the courthouse in Visalia and formed the Tulare Valley and Giant Forest Railroad Company, which might have led suspicious Visalians to believe they were part of a scheme by the despised Southern Pacific Railroad to obtain and exploit the forest land.

George Stewart, like many Tulare County men, had long been concerned with land matters. Born in Placerville, California, in 1857, Stewart had come to Tulare County with his family in 1866. They were farmers, but young Stewart eventually learned the printing trade and at 19 years of age found a job working for one of the local newspapers, the Visalia Delta. Within a few years he became a city editor, and his promising journalism career soon took him to San Francisco and Hawaii before he returned to Visalia to run the Delta. Stewart had begun writing editorials urging preservation of mountain watersheds not long after the passage of the Timber and Stone Act of 1878, and many Central Valley citizens shared his concern for what might happen with so much forest land open for sale. As editor of the Visalia Delta and a prominent businessman, Stewart was acutely aware of the issues that concerned his readers, and land — its uses, its value, its legitimate or fraudulent acquisition — was a very big concern.

Stewart also mentioned other reasons he and J.D. Hyde, the Register of the Visalia Land Office, became suspicious:

Fourteen of the members [Stewart recalled] were not citizens of the United States, but made declarations of their intention to become such, in order to be able to apply to enter the lands. The names of several of the applicants were foreign. Many of them appeared to be men who would not be expected to possess the sum of $400, the amount required to pay for the land after the period of publication.

If someone looks like a dummy entryman, sounds like a dummy entryman, and acts like a dummy entryman, they must be a dummy entryman. It was common knowledge that big corporations often employed this tactic. Foreign sailors arriving in San Francisco might be offered a few dollars, a jug of whisky, and even a night in a whorehouse in exchange for filing a land claim under the Timber and Stone Act on a corporation’s behalf. Before shipping back out, these sailors would abdicate title to the corporation — there were no restrictions on transfer of ownership — and in such a manner whole forests had been acquired. The appearance of Keller and his associates, many of whom were in fact sailors, would have easily suggested just such a scheme. Nonetheless, George Stewart published their notices in his newspaper and J.D. Hyde took their applications and filing fees, but the Land Commissioner in Washington, D.C., was contacted and alerted.

SUSPENDED

After 60 days, with notices of the claims printed in the paper, the members of the Land Purchase and Colonization Association could return to the Land Office and pay for their land, which would then be legally deeded to them.

In the interim [according to Keller’s recollection], certain influential citizens of Visalia took it upon themselves to report to the Interior Department that the people who had filed on these lands were poor and the money they had offered at the land office was not their own, that they were irresponsible, and that the claims should not be allowed.

J.D. Hyde had indeed contacted William Sparks, the Commissioner of the General Land Office in Washington, D.C., at the urging of Stewart and possibly other local citizens. As it turned out, Commissioner Sparks believed that large land and timber baronies were essentially “un-American” and so was more than receptive to suspicions of land fraud. Sparks strongly felt that fraudulent acquisition of land could result in a dangerous situation of “permanent monopoly.” Sparks’s somewhat radical warning would undoubtedly have found a sympathetic audience in Charles Keller and Burnette Haskell had they read of his fears of monopolists “creating the un-American system of tenant-farming, or dominating the timber supply of states and territories, or establishing conditions of feudalism in baronial possessions and comparative serfdom of employees.” While Keller and Haskell shared this contempt for powerful land monopolists, it is ironic that they themselves were suspected of being the puppets of such villains.

An inspector of the General Land Office, in the course of his duties, looked into the matter and filed a report from Visalia on December 1, 1885. In the report, Inspector G.C. Wharton echoed local concerns, pointing out that the land was considered inaccessible and that no access could ever be had except through the expenditure of large sums of money by some giant corporation. Wharton also wrote in his report that he “could not learn that these parties had ever visited or examined the land upon which they had filed” and surmised that “these men are what are usually called ‘dummies,’ engaged by some corporation, thus evading and violating the law.”

Later that month, just before the first group of applicants was due to present final proofs and tender, the Visalia Land Office received a letter notifying Hyde that Sparks had suspended the claims until a regular investigation could be conducted. Four large tracts (called “townships” in the nomenclature of land management) containing the land in question, along with several additional townships, were withdrawn from entry. Sparks gave as his reasons “supposed irregularities in the surveys, and alleged fraudulent entries,” and promised “an examination in the field… as soon as possible.” In a state with a legacy of questionable land grabbing and bureaucrats who either looked the other way or winked while handing out claims to speculators and sharpers, the suspension of the colonists’ claims was a surprising action. Such a preemptive strike against suspected land fraud was a rarity. When Keller and the rest returned to find the applications suspended and the registrar refusing to accept payment for the claims, they had to be in a state of utter disbelief.

Upon this action by the Land Office, a meeting was held wherein the members of the association, who had all filed legal legitimate claims to the forest land, debated what had best be done in the face of such extraordinary circumstances. Confident that any investigation of them would clear them of all fraudulent intent, the would-be colonists decided to proceed with plans.

SOURCE NOTES: The Charles Keller papers and a number of books, including The Way It Was (Tulare, California, 1976) and Land of the Tules (Valley Publishers, Fresno, California, 1972) by Annie Mitchell; Our National Parks, by John Muir (Houghton Mifflin Co. Boston, 1901); and Marc Reisner’s Cadillac Desert: The American West and Its Disappearing Water (Penguin Books, 1993) contributed to this chapter. An unpublished thesis by Milton Greenbaum, “History of the Kaweah Colony” (Sequoia National Park library) and his citing of the Report of Inspector G.C. Wharton to the Commissioner of the General Land Office contributed to the understanding of what happened, as did letters from George W. Stewart to Colonel John R. White found in the George Stewart Papers (Visalia Public Library).