A History of the Kaweah Colony: A Challenge to Optimism

By Jay O’Connell. This 3RNews version as published August 2020.

We hear today that our whole forest and Avalon are made by Congress into a park. Most of the colonists are sick. (Annie Haskell’s diary, October 21, 1890)

It took three full weeks before news of Sequoia’s sudden enlargement reached those who had done so much toward realizing its establishment. George Stewart’s Visalia Delta reported on October 23, 1890, that it was a “surprise to many to know that the park comprises seven townships instead of two townships and four sections as at first supposed,” although the paper noted it had always been the intention of the originators of the bill, of whom Stewart was certainly one, to secure reservation of a greater area.

The Visalia newspaper undoubtedly spoke for Stewart personally when it explained:

Those who have expressed dissatisfaction at the limited scope of the original Vandever park bill, in that it did not take in enough sequoia forests, cannot attribute it to narrowness in the conception of the originators of the movement. There was little sequoia timber remaining in the possession of the government, and there was no desire to interfere with vested rights or with those who had made application for timber land containing sequoias under the laws of the United States.

VANDALS OF CAPITALISM

As news was so slow in making its way west from the nation’s capital, one might surmise that Andrew Cauldwell’s September 26 report recommending inclusion of Giant Forest and the surrounding townships into the park could hardly have made it all the way from Visalia to Washington in sufficient time to have had a causal effect on the park’s enlargement. Obviously, there were others of influence in the capital who evidently shared Cauldwell’s views, regardless of ever having read his report. But most people in Tulare County were little concerned with just who was responsible for the last-minute expansion of Sequoia — few people except those who were most dramatically effected by the news.

Burnette Haskell certainly had his theories. He claimed the purpose of the bill was “part of a plot to destroy Kaweah.” In the November 1, 1890, issue of the Commonwealth, Haskell explained:

The whole great San Joaquin Valley as a lumber market is in the hands of a gigantic lumber trust who have long watched us with a jealous eye. They well knew that as soon as we began producing lumber it would be sold at reasonable prices to the farmers of the valley and that their own prices would come down. Knowing also that our legal title to our lands was unassailable and seeing that we had at last got to the timber they did what monopoly always does under similar circumstances.

Haskell maintained that said monopolies had “flooded the colony with rumors that this bill takes away our lands.” Of course, Haskell set the picture straight for Commonwealth readers. Aspects of his theory he couldn’t explain — such as how the hated lumber trust had been behind the legislation expanding the park — he ignored. And aspects he disagreed with — such as his assertion that their legal title to the land was “unassailable” — he simply changed. (Title was only unassailable in that there was no title.)

Haskell was able to maintain his optimism and, in fact, presented a good argument for continued optimism. When on October 25, 1890, the Commonwealth finally reported on the California parks bill and Sequoia’s sudden enlargement, Haskell noted that while it “takes a portion of the Colony lands,” it also “reserves the private rights and interests of the settler.” Even the Delta agreed with this when it noted the provision in the bill honoring “any bona fide entry of land made within the limits.” “This is as it should be,” the Delta editorialized, adding that the “rights of all applicants who made their filings in good faith should be respected and protected by the government.” It is obvious the Delta was specifically speaking of the colonists.

Haskell wrote in the Commonwealth, steeling the resolve of the Colony:

Very well, then we propose to stay. Our colonists can rest easy. Our legal rights will be protected. Our homes preserved inviolate. The home of the American citizen is a sacred precinct, not to be invaded by the vandals of capitalism at their pleasure.

KAWEAH ON THE MOVE

The autumn of 1890 was a pivotal time for the Kaweah Colony. In addition to the creation and enlargement of Sequoia National Park and the arrival of the Haskells as permanent residents, the entire settlement was relocated down canyon to Kaweah Townsite.

Until that busy fall, the primary settlement of the Colony had been Advance, originally a road camp about four miles upriver from where road construction began. Perched on a bluff with limited level land available, it was never really thought of as a site of the permanent Colony town. Indeed, most of the time the colonists lived there as mere squatters, although eventually some of the members actually filed homestead claims at and near Advance.

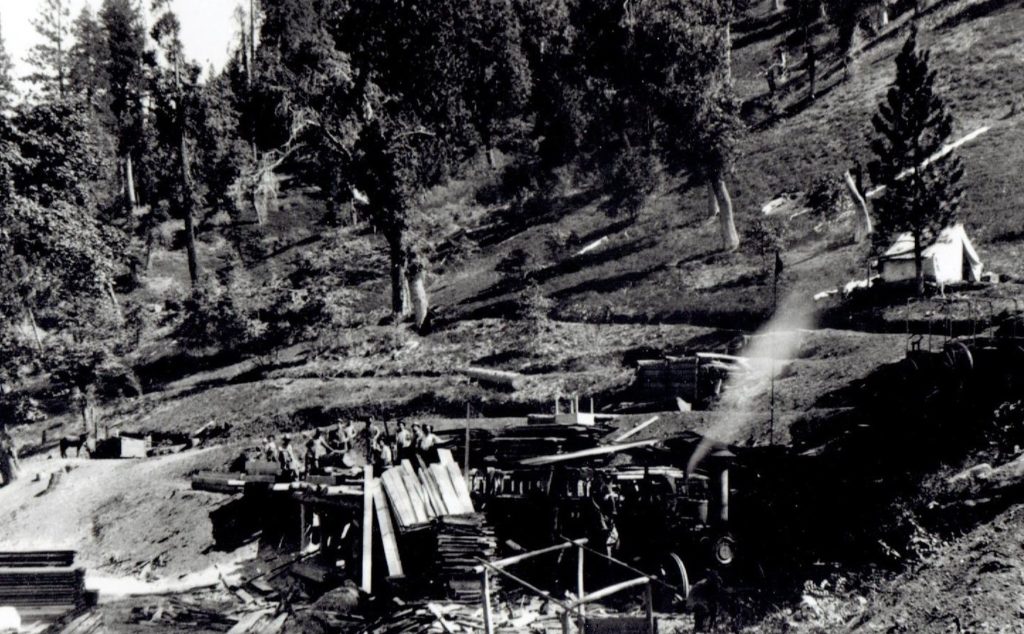

Before mid-1890, the Colony planned on eventually moving to a proposed town site at East Branch (as they called what is now known as Yucca Creek). This area, also known as Avalon by the Colony, was already the center of their agricultural endeavors. They dry-farmed and harvested hay there, had planted several small orchards and had begun work on a ditch and flumes for irrigation. After completing the road to the timber, they even built a spur road down to the confluence of East Branch (Yucca Creek) and the North Fork of the Kaweah River, but just as that road was being completed a change in plans was prompted by the arrival of Comrade Irvin Barnard.

Barnard’s financial assets have already been considered in telling of his Ajax steam engine, and further evidence of his means can be shown in a purchase he made of a 240-acre tract of land at the lower end of the North Fork canyon for $2,000.

The canyon broadens here—with calm incline

The hills up-billow from the oak clad plain;

The river ripples blithely over stones

Or rolls thru pools with soothing undertows.

This was how poetically inclined colonist Will Purdy described the area of the new settlement.

By late September, the big move had begun. The Colony newspaper noted that about 35 persons were already living at Kaweah Townsite. “As a place of residence,” they proclaimed, “it seems to be a favorite.”

In November, the Commonwealth gave some idea of the layout of the Kaweah Townsite:

The post office will be located in one third of the annex to the printing office and residents will have to call for their mail. The store building will contain the store, the treasurer’s office and reading room, with shelves for the colony library and files for papers. School will open in the school-tent on the hill south of the printing office. The blacksmith shop was moved to Kaweah where Vulcan Dudley will be nearer the river water that he loves so much.

By late November, the move was mostly complete. The Commonwealth reported that “the new town is growing in rapidity and now looks on both sides of the river somewhat like a country city.” Advance, by that time, had become almost entirely deserted and had “quite a desolate air.”

THEY KEEP CUTTING

After the Colony claims became a part of the new national park, Special Land Agent Cauldwell remained involved in the case and, in fact, matters heated up considerably between this agent of the government and the Kaweah Colony.

On October 25, 1890, Cauldwell reported to the Department of the Interior that the colonists were continuing to cut timber on land now embraced in the forest reserve. In letters dated October 30 and November 10, the honorable William Vandever, according to Cauldwell’s account, directed the Land Office to thoroughly investigate allegations that the Kaweah Co-Operative Colony Company was cutting within the reserve. Vandever allegedly instructed Cauldwell to “warn the trespassers to desist from further cutting and if they fail to do so lay the facts before the U.S. Attorney.” By this time, Cauldwell had already gone to Los Angeles to consult with the U.S. Attorney, W. Cole, and “received from him the necessary instruction on how to proceed should I be ordered to stop the depredations.”

On November 12, Cauldwell received his official orders and paid a visit to James J. Martin. Martin maintained a Colony office in Visalia in the same building, ironically, as the local Land Office. It was there that Cauldwell paid the Colony secretary and trustee a visit, asking if his company intended to continue sawing timber in the park reserve. Martin, a man with an air of distinguished sophistication, didn’t hesitate in answering in the affirmative.

I then and there [Cauldwell wrote] officially notified said James J. Martin, a manager of the Kaweah Colony Company, to desist from cutting of timber on said forest reservation. In reply he said he didn’t think they would, as they were cutting the timber under legal advise.

Martin, in his proper English accent, went on to inform Cauldwell that he could only give a definitive answer after calling a meeting of the trustees.

On November 24, Martin delivered that definitive answer. He informed Agent Cauldwell, in no uncertain terms, that the Colony was cutting timber on one of their own claims, and that they would continue to cut timber upon their claims in the forest reservation until restrained from doing so by force.

ARRESTED!

On December 4, 1890, the Tulare County Times reported that “B.G. Haskell, H.T. Taylor and William Christie were arrested in Kaweah for illegal lumber cutting.” A fourth trustee, James J. Martin, was “picked up” in Visalia. Annie Haskell’s diary provides this firsthand account:

Well, there has been quite a sensation. There were two deputies—and they were very nice. They have all gone to Los Angeles and will have to find bail. Mrs. Taylor felt awfully badly—she was crying and so Lizzie and I tried to comfort [her]. Burnette sent word for me to teach the school in his absence.

After Martin had informed Cauldwell that they would continue to cut until restrained by force, the government agent at once “proceeded to lay the facts before the U.S. Attorney.” Cauldwell’s report for November 26, 1890, shows the vehemence with which he now opposed the Colony:

In my judgment said trustees are the proper ones to proceed against, as the rank and file of the colonists simply obey their orders. It is a socialist organization, in my opinion, under semi-military rule. The majority of its members are un-naturalized foreigners.

These comments were quite in contrast to Cauldwell’s first report filed in July, wherein he claimed the colonists appeared to be “a wonderfully ‘happy family’ of enthusiasts” and that so far as he could observe they were “above the average in intelligence.” Cauldwell also claimed he could not but help “testifying to their industry and perseverance in overcoming almost insurmountable difficulties in building their road.” There is no readily apparent explanation for his drastic change of heart.

In any event, Cauldwell’s new opinion of the Colony and his recommendations to the U.S. Attorney resulted in the arrest of the Colony trustees. After posting bail, they still faced the expense of returning from Los Angeles, 200 miles away, as well as the cost of another future trip south to stand trial. While the other trustees were back in Kaweah well before Christmas, Haskell remained in Los Angeles and, as the holiday season approached, prepared for their impending trial.

In response to her suddenly absent husband’s request, Annie Haskell took charge of the school at Kaweah. The Colony had long been boastful of its school. Although Comrade Vest, who held a certificate in the California Department of Public Schools, failed to have Advance and its neighborhood declared a School District by the state early in 1890, he continued to maintain a school that was “conducted in accordance with the educational system of the state of California.” Vest had demanded legitimacy even if he couldn’t obtain county funds.

When school resumed in September 1890, Vest was pleased to announce that “he now had fifty-two pupils enrolled.” One of those pupils, Will Purdy, remembered fondly a supportive environment maintained at the school:

The wise preceptor, ardent as the rest

Bore the unpoetic name of Vest

His youthful charges openly exprest

For buoyant spirits never were suppressed

But their energies were skillfully directed

Into channels safe that were connected

With useful projects, the constructive kind

that develop both the body and the mind.

But that autumn Vest left Kaweah to take a job in Visalia as a school principal. Superintendent of Education Burnette Haskell had a difficult time keeping the post of Colony teacher filled.

The teachers [Haskell once wrote] found it impossible to enforce discipline when a child, who deemed himself aggrieved, would in the class openly threaten that he would go home and get his father to call a meeting and remove the instructor. The boys and girls alike called the teachers by their first names and came to school or not as they pleased. Complaints made to the parents were of no avail whatever, corporeal punishment of children being a “relic of barbarism.”

Annie, who later would become a career teacher, wasn’t particularly thrilled with teaching at the Colony school that December. In fact, she hated it. She wrote in her diary that the children “behave most abominably and the accommodations are so bad and books so scarce that on the whole I am liable to have a very miserable two weeks of it.” She described the school tent as “cold” although they finally “got a nice stove put in there.” She herself sounded like a schoolgirl when she wrote “oh how glad, glad, glad I was that it is Friday night.” And just before the holiday vacation, her diary exclaimed “Thank Heaven! School is to end. I do hope I shant have to teach after the holidays.”

CHRISTMAS AT KAWEAH

Annie Haskell wrote in her diary on December 24, 1890:

Christmas Eve. If Burnette were here I should be satisfied. I have just put some candy in the baby’s stocking. I sent down one box for the tree tomorrow eve, and there will be a knife for him. He will fare slimly compared with other Christmases, but he will probably be just as happy.

It was her first Christmas at Kaweah. With her husband away, Annie lamented that for her it would “not be a very merry Christmas.” She had only been at Kaweah for a few months and was finding it difficult to adjust. Still, she admitted in her diary that next day, “Mr. Martin did all in his power to make this a delightful day.”

The Kaweah Commonwealth offered a description of the holiday celebration shared by the community:

Committees were appointed on arrangements and decorations, a fund was made up, someone was sent to Visalia to buy necessary presents, candies, nuts, etc. and a large fir tree was brought down from the Mill Camp for a Christmas tree. The hall was decorated with evergreens—pines and cedar brought down from the Mill Camp. A stage had been made for the event, upon which the Christmas tree was placed and decorated. The piano was brought over from the restaurant, and Miss Abbie Purdy and Mr. Clark, our violinist, were the musicians of the evening.

The program consisted of recitation and songs by the children, a juggling exhibition by Al Redstone, and a dialogue between Frank and Harry Jackson representing an interesting conversation between father and son. After “Santa Claus” had made all the children happy with a bestowal of useful as well as ornamental presents, and after everybody in the room had been abundantly provided with cakes and candies, nuts and raisins, the room was cleared once more and those remaining tripped the “light fantastic” until the “wee small hours of the morning.”

Annie hardly felt like tripping the light fantastic, as the saying went, but she did note in her diary how “Roth enjoyed himself to say the least.” Her entry for Christmas Day continued with an account of their first Kaweah Christmas and the wonderful time her five-year-old son enjoyed:

First, he had some candy in his stocking, and he kept exclaiming “ain’t Santa Claus good!” Then Hambly brought up a great package from Uncle Benjie which contained a box of three pies, a fine food basket, and a trumpet and candy cane.

Then this p.m. we went down to the restaurant where we enjoyed a nice turkey dinner, then we waited for the Christmas tree. Before the presents were distributed the children sang three songs and then this wonderful Santa Claus appeared. I watched Roth. He was awe-stricken and when presented with his presents said “Thank you, Santa Claus.”

Annie closed her Christmas entry with a reminder of why the holiday season can be so sad for so many. “If Burnette had only been there,” she wrote. “Poor old dear.” For Annie, these feelings of loneliness were an increasingly common refrain. While life went on for her at Kaweah alone, her husband remained in Los Angeles preparing for a trial that could very well determine the fate of the Colony.

SOURCES: Colony documents used as source material for this chapter include a circular issued by the Board of Trustees on January 24, 1891, entitled “To Whom It May Concern” (Visalia Public Library) and various issues of The Kaweah Commonwealth. Annie Haskell’s diaries, Will Purdy’s “Kaweah: The Saga of the Old Colony,” and Agent Cauldwell’s Report to Commission, General Land Office were also consulted. Other sources were contemporary reports in the Visalia Weekly Delta and Haskell’s 1902 Out West article “Kaweah: How and Why the Colony Died.”